People

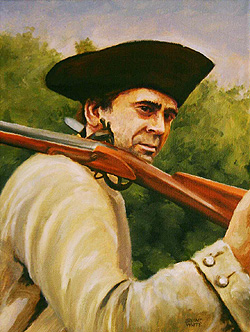

Jason Parmenter

1734-181?

Jason Parmenter

© 2008 Bryant White

Prologue

Jason Parmenter was born in Sudbury, Massachusetts, a fourth generation descendent of Deacon John Parmenter who came to Sudbury in 1639. Little is known of Jason's early life beyond his birth on January 1, 1734. As a young man, Jason moved with two brothers to northwestern Massachusetts, eventually settling to farm in the newly incorporated town of Bernardston. At a time when most men delayed marriage until their mid-twenties or later, Jason was only 19 when he wed Abigail Frizzell, originally of Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, on March 7, 1753. (1)

Patriot

Jason was 39 years old when the first shots were fired at Lexington in 1775. Haying season was approaching and Abigail was expecting another child in early fall, but this did not prevent her husband from volunteering as a private in a local militia company under Captain Agrippa Wells for a tour that lasted from May 1 through September 23, 1775. Wells' company was part of a regiment commanded by Colonal Asa Whitcomb that marched to Cambridge to support the siege of Boston. Jason would have been in Cambridge during the Battle of Bunker Hill and probably witnessed General George Washington's taking command of the army in July, 1775. (2)

Jason had no sooner returned home than he was serving another militia tour, this time as a corporal in New York, at Fort Ticonderoga. As part of the Ticonderoga garrison, he would have come into contact with what was left of the American forces who had invaded Canada the previous year under the command of Benedict Arnold and Richard Montgomery. When Jason arrived in September 1776, Arnold was engaged in a desperate holding action on the Lake Champlain to slow down the British army in its advance into New York. The snow was already falling when Corporal Parmenter returned home in November, 1776. (3)

The following July, in 1777, Jason's militia duty took him to the Hudson River where he may have met troops retreating from Fort Ticonderoga in the face of the advancing British army under General John Burgoyne.

Fort Ticonderoga, the first object of Burgoyne in 1777.

Courtesy Fort Ticonderoga Museum, Ticonderoga, NY

So far, Jason Parmenter had been remarkably fortunate, escaping injury, battle wounds or sickness on any of his militia tours. Tragedy struck the Parmenter family, however, when the eldest son volunteered in the late summer of 1777. Jason, Jr., was "taken out into the eternal world by a cannon ball" during a battle with British forces at the southern end of Lake George that September. He was just 16 years old. (4)

Only a few weeks later, his grieving father joined the flood of New England men pouring into Vermont and New York to halt the British advance. Jason witnessed the surrender of Burgoyne at Saratoga in October, 1777. (5)

American artist John Trumbull painted this famous scene of the surrender of General John Burgoyne to General Horatio Gates and the American Army.

Courtesy Capitol Rotunda, US Government, Washington DC

The Saratoga campaign was the last militia duty Jason would undertake. For the rest of the war, he worked from the home front, serving on Bernardston's Committee of Correspondence, and recruiting for both the militia and the Continental Army. (6) As a town officer and resident, he also was asked to vote on whether or not Bernardston supported an effort to create a new constitution for the state of Massachusetts.

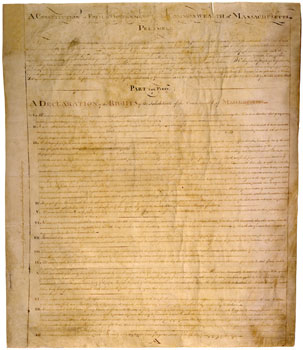

Citizens had roundly rejected the legislature's first attempt to create a state constitution to replace the old Crown charter. The second proposed constitution was more than a little controversial. Many people, especially those living in central and western rural communities like Bernardston, objected to what they perceived as an eastern bias and aristocratic elements, such as stiff property qualifications for holding office and the creation of a Senate. Despite these objections, the constitution, mainly the work of John Adams, was ratified at the world's first constitutional ratifying convention in 1780. It is the oldest active democratic constitution in the world. (7)

Celebrated today, the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 was more than a little controversial in the 1780s. Many western towns did not approve of the property qualifications for office holders and the proposed state senate.

More info

War's End and the Regulation

Like other Americans, Jason Parmenter and his neighbors greeted the end of the war with relief; however, that relief and whatever optimism accompanied it, quickly faded. A severe recession spelled trouble for everyone, especially farmers who had land and goods, but not ready cash. Times grew worse and money became scarcer still. Lawsuits for debt mounted. As a constable and tax collector for the town of Bernardston, it was Jason's responsibility to attend the auctions of real estate seized from those who could not pay their taxes. Because of the deflated economy, property often sold for only a third of its actual value. Like many of those around him, Jason was increasingly disenchanted with a state legislature and governor who seemed not to care that citizens were losing their land, along with their economic and political independence. At some point in the late fall of 1786, Jason Parmenter moved from disapproval of government policies to active opposition. He decided to join the Regulators, the men who would become known to their opponents as "Shays' Men," "the Insurgents" or, simply, "the mob." (8)

Few men endured more hardship or personal tragedy as a result of their participation in Shays' Rebellion than Jason Parmenter. His war service and town offices understandably pushed him into a leadership role once he became a Regulator. As towns mobilized thousands of men across the region, Jason emerged as a "Captain with the insurgents" according to a government history of the movement. While we do not know if Jason participated in the court closings that began in the fall and continued into the winter of 1787, it is certain that he marched with the Regulator regiments that assaulted the United States Arsenal at Springfield on that bitter cold, late afternoon on January 25.

Jason Parmenter and other Regulators broke ranks in the face of withering artillery fire. Not a musket was fired on either side.

© 2008 Bryant White

Like many of his comrades, Jason may have imagined that they would march triumphantly, colors flying and drums beating, onto the Arsenal grounds. Instead, the Regulators were shocked when the commander of the local militia, General William Shepard, ordered his artillerymen to fire "at waistband height." The murderous artillery barrage of cannonballs and grapeshot dispersed the Regulators, and Parmenter joined in the pell-mell retreat to Pelham. At some point over the several days the Regulators spent at Pelham, Jason decided to go home to Bernardston. As a result, he missed the government's pursuit and rout of Daniel Shays' remaining men at Petersham on February 3.

Despite escaping the disaster at Petersham, Jason Parmenter realized that, as a known Regulator leader, he was a marked man. By taking up arms against the government, he had committed treason, a capital offense. Jason took no chances; he prudently decided to escape across the border into neighboring Vermont, rather than risk arrest for treason in Massachusetts.

Parmenter was relatively safe in Vermont. Many of people there were sympathetic to the Regulators since they were experiencing similar problems of their own. After two weeks of exile, Jason embarked on what turned out to be a disastrous course of action. On the evening of February 17, he decided to slip back into Bernardston to gather some of his possessions. As he approached the state line in Northfield, Parmenter and his companions literally ran into a group of mounted government men who had a warrant for his arrest. Shots were fired; Parmenter and his men fled. When Jason returned in the morning, he was horrified to see blood on the snow. Since none of his own party had been wounded and his was the only gun that had been fired, Jason knew that he, and he alone, was responsible for the blood-stained snow. He broke down and cried. He knew in that moment he may have taken a life and that this tragedy would seal his fate. There could be no pardon, now.

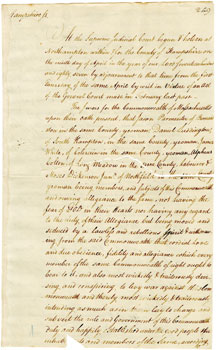

When Jason was arrested later that day, he learned that the man he had shot, and killed, was Jacob Walker of Whately, a sergeant in the government militia. Jason Parmenter was jailed in Northampton to await trial along with six other Regulators being tried for high treason, including 36-year-old Henry McCulloch of Pelham, a man believed to be one of Daniel Shays' closest associates. (9)

All six men were found guilty and all six were sentenced to death. The court, however, decided it was best to show leniency and execute only two men as an example. The choice was an obvious one: Jason Parmenter and Henry McCulloch were to be hanged on May 24, 1787, in Northampton, the county seat.

The Supreme Judicial Court sentenced Jason Parmenter and Henry McCulloch to death for high treason.

More info

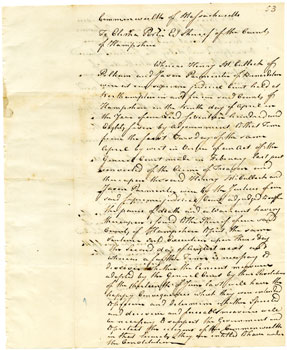

While Parmenter suffered agonies of mind in jail, his friends and relatives peppered the Governor and legislature with petitions pleading for mercy on Jason's behalf. Jason himself petitioned Governor Bowdoin, referring to his war record, his faithful service as a citizen of the Commonwealth, and the fact that he had never intended to kill Whately. He had fired, he wrote, from "the effect of surprise and that he never intended to take his [Whately's] life or the life of any of his fellow creatures." Thirty townsmen wrote the Governor that Parmenter had been a minor player at most in the recent rebellion and should be pardoned or at least granted a stay of execution in order to put his affairs in order. (10)

Other activities on Parmenter and McCulloch's behalf were more ominous. In Warwick, a local physician was taken hostage and his captors left a coffin left behind with a note threatening to kill him if the sentence of execution was carried out. (11) Unconcealed resentment and threats of violence encouraged Governor Bowdoin to issue a one month stay of execution. But on June 21, the newly appointed day, the government was ready for trouble. An extra detachment of troops was present in case of a rescue attempt or other violence. An armed guard delivered Parmenter and McCulloch to the meetinghouse where the Reverend Moses Baldwin of Palmer delivered the execution sermon. The building was full to the rafters and a crowd gathered around the windows. Following the service, Parmenter and McCulloch were taken to the gallows erected for them. (12)

The two men climbed the scaffold wearing the ropes that would hang them. Their hands were tied and their faces covered. A spectator reported that there was hardly a sound "except the deep breathing of the multitude." Sheriff Elisha Porter of nearby Hadley stood by, ready to give the final word to the hangman. With exactly one minute remaining, Porter announced that the government in its mercy had extended another reprieve to both men. This proved too much for Jason Parmenter: he fainted on the scaffold. (13)

Sheriff Elisha Porter of Hadley obeyed the Legislature’s order to delay announcing its decision to reprieve Parmenter and McCulloch until the last possible moment.

More info

Back in the Northampton jail, Jason would be reprieved twice more. Meanwhile, elections had ousted Governor James Bowdoin in favor of the ever-popular John Hancock. In September, 1787, Governor Hancock pardoned both Jason Parmenter and Henry McCulloch. (14)

Epilogue

His ordeal had a powerful impact on Jason Parmenter. Although known to all of his neighbors as "Captain Parmenter," he abhorred violence of any kind. He sold his property in Bernardston and bought land in nearby Leyden, originally part of Bernardston, near his eldest surviving son, Reuben. Formally a Presbyterian, he became a member of a utopian sect in the 1790s. Called the Dorrellites, after their leader and messianic founder, William Dorrell. The Dorrellites believed in non-violence and free love, and refused to eat meat or use animal products of any sort. Many other family members and neighbors were part of this sect, and Dorrell himself lived on Jason Parmenter's land. The Dorellites broke up in 1800, after their leader publicly recanted his beliefs during a dramatic confrontation with other town residents. (15)

Shoes and a cavalry saber belonging to William Dorrell, a former British soldier and a POW during the Revolution, and later the leader of the Dorrellites, a utopian sect. Reflecting the sect's beliefs, Dorrell's shoes are made of wood and linen; the leather wrapping his sword hilt has been removed.

When the Dorrellites disbanded, Jason moved to Stoddard, New Hampshire to live with his younger son, Asahel. After a final appearance in the 1810 census at age 76, "Captain Jason Parmenter" disappeared from the historical record.

About This Narrative

Note: All narratives about people are, to the extent possible, based on primary and secondary historical sources.

See Further Reading for a list of sources used in creating this narrative. For a discussion of issues related to telling people's stories on the site, see: Bringing History to Life: The People of Shays' Rebellion

| Print | Top of Page