Essay

Everyday Life - Making a Nation

Communities United, Communities Divided

Although the Massachusetts government commended General William Shepard for his "spirited defence" of the United States Arsenal during the Regulation, many members of his community never forgave Shepard for his actions that day.

In April, 1787, a correspondent reminded the editor of the Worcester Magazine that most citizens of the Commonwealth had not marched either with the Regulators or the government militia. These people, who "call[ed] themselves neuters, or good friends to government" thought the recent actions "all entirely needless" and believed the disturbances could have been "settled by gentle measures." (1)

Communities that had split during the Regulation tried to return to normalcy in its aftermath. Government supporters demonstrated their commitment to the consensus and unity their towns prized by helping Regulators at risk of arrest and prosecution return home safely. Park Holland of Petersham, who had marched with the government militia, earned the undying gratitude of a Regulator "who sprang to me for protection and beged I would not suffer him to be abused." Holland reassured "the poor man…I told him that he should not be Ill used and might stay at Home in peace." Similarly, Captain Hugh McClellan of Colrain had stood with the government militia at the Springfield Arsenal against many of his neighbors. That did not prevent McClellan from traveling to Boston to speak on behalf of a Regulator neighbor. In the process, he gained the gratitude and respect not only of the man he assisted, but of the whole town. In contrast, William Stevens, also of Colrain, did not act on behalf of his Regulator neighbors in the weeks following the collapse of organized resistance. A relative newcomer to Colrain, he encountered implacable resentment and hatred for the role he played in firing the Arsenal artillery. Within a few years, Stevens left Colrain for New York.(2)

The potential for renewed strife and violence resurfaced as the hour approached for the execution of the men convicted of high treason against the state. Officials and government supporters received ominous threats, such as this message left at the door of Sheriff Caleb Hyde of Pittsfield:

I understand there is a number of my countryment condemned to die because they fought for justice I pray have a care that you assist not at the Execution of so horrid a crime, for by all that is above, he that condemns and he that executes shall share alike. So no more at present but prepare for death with speed, for your life or mine is short, when the woods are well-cover'd with leaves I shall return and pay you a short visit. So no more at present but I remain your most inveterate ENEMY(3)

As they worked to save convicted Regulators, communities reaffirmed old ties and loyalties. In the case of Henry McCulloch of Pelham, condemned to hang for high treason, the entire town petitioned "to avert, if possible his impending Fate." Participating in efforts to pardon convicted Regulators offered an opportunity for government supporters to demonstrate their community and personal loyalty. The town of Amherst turned out many Regulators, but unlike many of his neighbors, Sheriff Ebenezer Matoon had opposed the Regulation. As a consequence, he had "Suffered much in Person & proper[ty] by these People, I have been obliged to move my family to a Neighbouring Town for Shelter." The Amherst sheriff, however, wrote a moving letter on McCulloch's behalf, informing Major Thomas Cushing that "Notwithstanding all this I must beg for Mc Colloch, and I wish to - Interest you in his behalf."(4)

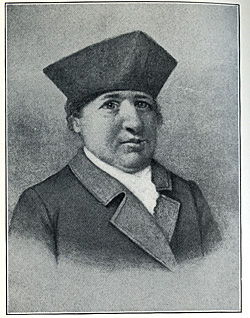

A poignant example of a permanent rift between an individual and his community in the aftermath of the uprising was the experience of General William Shepard of Westfield. On the surface, Shepard, a Continental Army veteran, was a hero. The House of Representatives passed a resolve in February 1787 commending his "exertions & spirited defence of the Federal Arsenal at Springfield against the attempts and attack of the Insurgents."(5) Within his own community, however, Shepard became a pariah, enduring criticism, death threats and gruesome reprisals. In a letter written three years later, Shepard told Henry Knox that his actions at the Arsenal had

Excited against me the keenest Resentment of the disappointed Insurgents, manifested in the most pointed Injurys, such as burning my Fences, injuring my Woodlands, by Fire, beyond a Recovery for many Years - wantonly & cruelly butchering two valuable Horses, whose ears were cut off and Eyes bored out before they were killed - insulting me personally with the vile Epithet of the Murderer of my Brethren, and, through anonimous Letters, repeatedly threatening me with the Destruction of my House and Family by Fire.- which kind of Injuries I occasionally experience even to this day.(6)

In contrast to Shepard's ordeal, Park Holland's neighbors did not forget his efforts on behalf of friends and neighbors in the days following the rout at Petersham. Holland in turn was gratified that "Shays party being well satisfied with my conduct towards them through the late disturbance they generally gave their Votes in my favor and I was chosen by a verry respectable" as a representative in the Massachusetts legislature the following spring.(7)

The violence and bloodshed of 1787 made communities anxious to reestablish and maintain the elusive harmony and consensus they prized. The following winter, towns across the Commonwealth sent representatives to vote on the proposed federal constitution created at Philadelphia. The ratifying convention passed the Constitution by a narrow 19-vote margin. Instead of vowing to continue their opposition, the delegates who had cast nay votes accepted their defeat and promised, in the words of one delegate, "to go home and endeavor to infuse a spirit of harmony and love among the people."(8)

| Print | Top of Page