For Teachers: Study Guide

Study Guide for

From Revolution to Constitution: Shays’ Rebellion and the Making of a Nation

A Bloody Encounter, © 2008 Bryant White

Introduction

The conflict that became known as Shays’[1] Rebellion is most known for a bloody confrontation at the United States Arsenal at Springfield, Massachusetts, on January 25, 1787. Yet, it is the conflict as a whole that presents the most dramatic example of the social, political and economic struggles of the years following the American Revolution. Shays’ Rebellion and the Making of a Nation explores essential themes of the period leading up to the creation and ratification of the Constitution, and enhances understandings of our national identity and origins. The overarching theme is the transformation of the United States of America from a government founded on state authority into one based on the authority of the citizens themselves—“We the People.” The website exhibit illuminates a forgotten but crucial period in our nation’s founding, when the survival of the republican experiment in government was neither foreordained nor assured.

Shays’ Rebellion raised crucial questions regarding the relationship of citizens to their government. It thus affords an opportunity to help 21st century Americans better understand the nature of their Constitution and how it came to be. The “Rebellion” loomed large in the minds of delegates who came to Philadelphia to find a solution to the crises destabilizing the fledgling nation. It presented the most dramatic example of the unrest and dissension occurring throughout the new United States that alarmed people across a wide spectrum of post-revolutionary society. Citizens understood that the American Revolution would mean both greater economic opportunity as well as the end of political oppression. For many, expectations were dashed while others railed against the social and economic mobility the American Revolution had unleashed. Because it involved fundamental economic, social, and political issues, Shays’ Rebellion forced ordinary Americans no less than elite leaders like George Washington, to think about their understandings of the promises of the American Revolution and what kind of government would fulfill them.

Making a Nation, © 2008 Bryant White

While scholars debate the precise nature and degree of Shays’ Rebellion’s influence, it undeniably played a role in the creation of the Federal Constitution. Although all of the states experienced fiscal hardship, disorder and at least the threat of unrest, the failure of Massachusetts to maintain order proved especially shocking to observers. Thomas Jefferson’s famous response that “a little rebellion now and then is a good thing” notwithstanding, many more were concerned that if Massachusetts with its celebrated republican government and constitution fell prey to anarchy, could the rest of the states be far behind? States that had not bothered to send delegates to the Annapolis Convention the previous fall responded to the news of Shays’ Rebellion by choosing men to attend the Philadelphia Convention scheduled for spring 1787. The events of the winter of 1786-87 loomed large in the minds of the delegates, including George Washington, who wrote in despair that winter from Mount Vernon to his friend General Henry Knox: “I feel… infinitely more than I can express to you, for the disorders which have arisen in these States. Good God! who besides a tory could have foreseen, or a Briton predicted them!”[2]

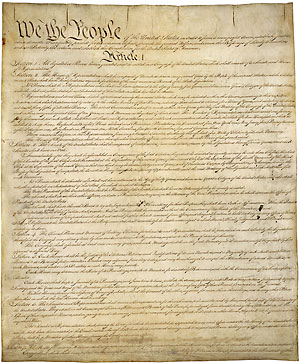

The US Constitution, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Shays’ Rebellion forced Washington and other Americans to rethink the Confederation system and the assumptions behind it.The events in Massachusetts fueled the desire among many political leaders to curb the excesses occurring in individual states. Political leaders reasoned that the people of the states, and, in some cases, the legislatures themselves, had proved unable to sustain their republican-based systems of government. This translated into a campaign to revise the Articles of Confederation and ultimately to discard them. The Articles were by design and intent weak; the real power in the loosely united confederation rested with the individual states. Rejecting a loose confederation, the delegates crafted the Constitution with a federal model of government immeasurably more powerful than that conceived under the Articles. Significantly, many of the powers denied the states in Article I, section 10 of the proposed Federal Constitution – such as the power to print currency and pass tender laws – were precisely those the authors felt had been abused by state legislatures.[3]

With the opening words, “We the People …do ordain and establish this Constitution,” the Founders expressly stated that the authority rested not with the state legislatures, but with the people themselves. This was very different from the Articles which spoke of a “perpetual Union between the States.” This radical new conception of the foundation of government made possible a sharing of authority between strong central and state governments. At the same time, the Founders built in safeguards that they hoped would prevent individual, group or private interests from overwhelming the public good. The anarchy Shays’ Rebellion seemingly presaged, coupled with what many delegates perceived as state-sanctioned assaults on liberties and property, culminated in a federal plan of government unlike any ever before seen or imagined. Now commonplace to 21st century Americans, the Constitution offered an innovative solution to the most pressing political problem of the 18th century: how to sustain a permanent and expansive republic when the best political science of the day declared such a system inherently vulnerable and short-lived. Shays’ Rebellion and its implications loomed large in the minds of the framers as they struggled to create a free and stable government strong enough to survive among the most powerful monarchies in the world.

Daniel Shays, © 2008 Bryant White

Denounced as desperate debtors and insurgents, the Massachusetts Regulators and their sympathizers share a lasting legacy in the creation of the Constitution itself; it is thus we who are ultimately indebted to them. It is no surprise that Daniel Shays, whose name has come to represent the Rebellion, has been seized upon as a symbol by Americans across the political spectrum. In their actions and protests, the Regulators (as they preferred to be called) raised fundamental questions about the relation of people to the government, how citizens participate in that government and the accountability of those who govern. Shays’ Rebellion is a powerful reminder that such questions have always been and will remain at the heart of the American experiment.

Questions

Questions to consider as you explore this website

- Like the other states, Massachusetts had participated in

a radicalizing event: the American Revolution. In the years leading

up to war and then independence, communities throughout Massachusetts

experienced turmoil and often violence as resistance to British

government and authority intensified.

What sorts of resistance to government occurred in Massachusetts in the 1770s? Compare this activity to the actions of the Massachusetts Regulators in 1786-87. In what ways are they similar? In what ways do you think they differed? - Shays’ Rebellion and internal convulsions in other

states occurred against an international backdrop. Independence

freed American traders and governments from the onerous obligations

of Britain’s mercantile colonial empire. By the same token,

however, independence cut Americans off from its protection,

including the British West India trade network, a mainstay of

pre-Revolutionary commerce.

What sorts of economic opportunities and challenges did the people and the government of Massachusetts face as the Revolutionary War ended? What policies did the Massachusetts government adopt in order to pay the state’s war debt? What impact did those policies have on its citizens? - By the mid-1780s, Massachusetts, like the rest of the new

nation, was in the throes of a severe depression. Communities

petitioned the state legislature with grievances and pleaded

for fiscal relief. Delegates from dozens of towns gathered at

County Conventions and issued resolves, including calls to amend

or revise the new Massachusetts Constitution of 1780.

What sorts of concerns did communities express in these petitions? What solutions did they suggest? How did the state legislature respond? - As towns continued to petition and town delegates attended

county conventions, many citizens decided it was necessary to

prevent the judicial courts of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts

from convening until the state addressed the grievances expressed

in the petitions. Other citizens believed it was their duty to

protect the courts and ensure that they could open.

What did the citizens who wanted to close the courts call themselves? How did they go about stopping the courts? How did the government respond? Who protected the courts? - By winter of 1786, protests were gaining momentum and members.

All eyes turned to the United States Arsenal in Springfield as

expectations grew that the Regulators would try to take over

the barracks and supplies there.

Why did the Regulators go to the Arsenal? Who got to the Arsenal first? What happened there? What sorts of decisions did General Shepard have to make? Why do you think the Regulators responded as they did? - As armed resistance ended in the winter of 1787, the Massachusetts

government offered a pardon to rank-and-file men who had taken

up arms. Men identified as ringleaders were imprisoned; several

were sentenced to death.

Why do you think armed conflict ceased? Did many Regulators take up the government on its offer of a pardon? What were the conditions of this pardon? Why do you think the pardon included restrictions on teaching school and running a tavern? On what charge were the imprisoned leaders condemned to death? When and why did the government decide to pardon them? - In the spring of 1787, delegates from every state except

Rhode Island attended a convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

to revise the Articles of Confederation, under which the national

government had been operating since 1781.

What sorts of problems did the delegates hope to address at the Convention? What role do you think the Massachusetts Regulation played in the creation of the new federal Constitution? What sort of role or influence do you think the conflict in Massachusetts played in the debates and in the final document? - In 1788, Massachusetts became the sixth state to ratify the new Federal Constitution when the Massachusetts ratifying convention voted to accept the proposed plan of government. How many delegates to the Massachusetts ratifying convention voted to adopt the Constitution? How many voted against it? Do you think former Regulators were more likely to oppose or to support ratifying the Constitution? What about their opponents?

- In the years following the ratification of the Federal Constitution,

the turmoil of the mid-1780s faded into memory, and became known

as “Shays’ Rebellion.”

Who was Daniel Shays? How and why do you think his name became synonymous with the Regulation? Do you think what happened in 1786-87 in Massachusetts was a rebellion? Why or why not? Consider the concerns expressed by the Regulators, their sympathizers, and the supporters of the Massachusetts government during the Regulation. Do you think any of these any of these issues are still relevant today? If so, which ones? - On February 4, 1787, government militia under the command

of General Benjamin Lincoln surprised and routed a force of Regulators

led by Captain Daniel Shays in Petersham, Masachusetts. A monument

erected in 1927 to commemorate this event bears the following

inscription:

"In this town on Sunday morning, February fourth, 1787, Daniel Shays and 150 of his followers, in rebellion against the commonwealth, were surprised and routed by GENERAL BENJAMIN LINCOLN in command of the Army of Massachusetts, after a night march from Hadley of thirty miles through snow in cold below zero.

"This victory for the forces of government influenced the Philadelphia Convention which three months later met and formed the Constitution of the United States.

"Obedience to law is true liberty."

A second monument was erected in 1987 with this inscription:

"In this town on Sunday morning, February fourth, 1787, CAPTAIN

DANIEL SHAYS and 150 of his followers who fought for the common people

against the established powers and who tried to make real the vision

of justice and equality embodied in our revolutionary declaration

of independence, was surprised and routed, while enjoying the hospitality

of Petersham, by General Benjamin Lincoln and an army financed by

the wealthy merchants of Boston.

"True Liberty and Justice may require resistance to law."

What is similar in these inscriptions? What is different? What

changed between the event itself, the period in which the first monument

was erected, and the time in which the second monument appeared in

Petersham? Is one interpretation more “true” than the

other? What sort of inscription might you compose to describe this

event?

[1] Shays’ versus Shays’s: we are aware that in the academic literature Shays’ Rebellion has been punctuated both as Shays’s and Shays’. Grammatically either is correct; and, after discussion with scholars, we have decided to use the Shays’ punctuation, as it is more accessible to the general public.

[2] George Washington to Henry Knox, 26 December 1786, The George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division.

[3] See, for example, James Madison’s Vices of the Political System, in Jack P. Greene, ed. Colonies to Nation, 1763-1789: A Documentary History of the American Revolution (New York: W.W. Norton & Company 1975) pp. 514-19.