People

James Bowdoin

1726-1790

James Bowdoin, II

By Christian Gullager, 1791. Courtesy, Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Bowdoin, ME. Bequest of Mrs. George Sullivan Bowdoin (through descent from Mrs. Sarah Bowdoin Dearborn)

James Bowdoin had a reputation as a strong supporter of free government. Elected to the Massachusetts General Court in 1753, he had sided with the opposition to Britain during the 1760s and 1770s. He helped to lead efforts to create a republican constitution for his newly-independent state, and served as the president of the constitutional convention that ratified the Massachusetts Constitution in 1780. Those triumphs must have seemed far in the past to Bowdoin when he was elected to succeed John Hancock as governor in 1785.(1)

Governor Bowdoin could hardly have chosen a more difficult time to serve. Two years after the Revolution, Massachusetts, like the rest of the nation, was mired in a deep, post-war depression. Determined to honor the Commonwealth's large war debts and maintain its credit abroad, Governor Bowdoin supported rigorous budget measures, including heavy taxes. These policies made both Bowdoin and his administration extremely unpopular. By the summer of 1786, thousands of Massachusetts men were taking up arms against the government, closing down judicial court sessions across the state.(2)

When insurgents closed the Northampton Court of Common Pleas on August 29, 1786, Governor Bowdoin issued a fiery proclamation denouncing the disruption of the court as an attack on the government of Massachusetts:

this high-handed offence is fraught with the most fatal and pernicious consequences, must tend to subvert all law and government; to dissolve our excellent Constitution, and introduce universal riots, anarchy and confusion, which would probably terminate in absolute despotism, and consequently destroy the fairest prospects of political happiness, that any people was ever favoured with…(3)

Bowdoin called on fellow Massachusetts citizens to defend the state against the violence and anarchy he believed would flow from the actions of the insurgents:

as they would not deprive themselves of the security derived from well-regulated Society, to their lives, liberties and property; and as they would not devolve upon their children, instead of peace, freedom and safety, a state of anarchy, confusion and slavery,-- I do most earnestly and most solemnly call upon them to aid and assist with their utmost efforts the aforesaid officers, and to unite in preventing and suppressing all such treasonable proceedings, and every measure that has a tendency to encourage them.(4)

Bowdoin feared that if he did not take strong and immediate action, all that had been so dearly fought for in the Revolutionary War would be destroyed. He therefore urged

the necessity of speedy and vigorous measures being taken for the effectual suppression of the Insurgents, without which, the well affected might from a principle of self preservation, be obliged to join them, and the insurrection become general.(5)

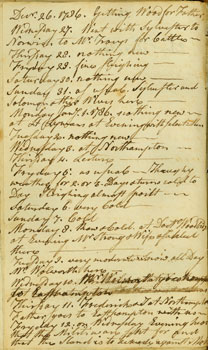

Jonathan Judd's diary gives a glimpse into the events in Hampshire County during

the month of January, 1787.

More info

Armed mobs continued to close courthouses throughout the fall. As the situation grew worse, Governor Bowdoin mobilized the militia to defend the Commonwealth. The General Court did not have time to raise the necessary money to support and pay the militia. As was customary in such emergencies, private citizens created a subscription fund to cover the costs until the General Court could raise the money. James Bowdoin's name headed the list of citizens pledging funds.

An army of over 4,400 volunteers marched west under the command of Revolutionary War veteran General Benjamin Lincoln to put down what Bowdoin and other leaders considered nothing less than an out-and-out rebellion. Meanwhile, Bowdoin's worst fears were realized when a column of 1,400 insurgents led by Captain Daniel Shays of Pelham marched on the United States Arsenal at Springfield, hoping to seize the muskets, artillery and supplies stored there. Only 1,200 local militia under the command of General William Shepard of Westfield stood between Shays' men and the Arsenal. Shepard's cool and able defense thwarted the attempt, and Lincoln's men arrived two days later. A combined night action swiftly dispersed the remnants of the insurgent army and forced them to retreat to Pelham. A final encounter with Captain Shays' men at Petersham on February 4 ended in defeat, surrender and flight for the rebels.(6)

On February 3, one day before the action at Petersham, Governor Bowdoin addressed the General Court of Massachusetts. Bowdoin described the steps he had taken to meet the threat to the state and urged the legislature to take the steps necessary to permanently quell the insurrection. Bowdoin described the insurgents as people taking advantage of a lenient government they believed unable to defend itself. It was of the utmost importance that the General Court act quickly and decisively. "Vigor decision and energy" on their part would "soon terminate this unnatural, this unprovoked insurrection, and prevent the effusion of blood":

This is so essential to the peace and safety of the Commonwealth, that it requires your immediate attention, and the speedy application of further means, if those already taken should be deemed insufficient for that purpose. Among those means You may deem it necessary to establish some criterion for discriminating between good citizens and Insurgents, that each might be regarded according to their Character, the former as their country's friends and to be protected, and the latter as public enemies, and to be effectually suppressed.(7)

Governor Bowdoin insisted that neutrality in this time of crisis was not an option. "At such a time as the present every man ought to shew his colours, and take his side, no neutral Characters should be allowed, nor any suffered to vibrate between the two." "Lack of action might, Bowdoin warned, "involve the commonwealth in a civil War, and all its dreadful consequences, which may extend not only to the neighbouring States, but even to the whole confederacy, and finally destroy the fair temple of American liberty; in the erecting of which, besides the vast expense of it, many thousands of valuable citizens have been sacrificed."(8)

Everything Bowdoin had done up to this point had been undertaken with the goal of quickly suppressing the insurrection, a strategy that had so far proved effective. The situation remained dangerously unstable, however. Massachusetts could not falter in its resolve:

if indecision, languor, or disunion should on this occasion pervade our public counsels, insurrection, though checked for the present, would gain new strength and like a torrent might sweep away every mound of the Constitution, and overwhelm the commonwealth in every species of calamity. In such case, if brought on by remissness, or relaxation on our part, we should be not only involved, most essentially involved, in that calamity, but justly chargeable with betraying the trust reposed in us by our fellow citizens, and chargeable with ignominiously deserting the posts assigned us, as guardians of the peace, the safety and happiness of the Commonwealth.(9)

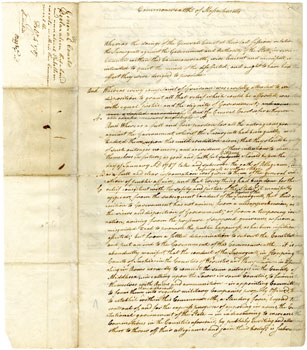

Declaration of the General Court that a Rebellion Exists. On February 4, 1787, the

General Court declared that "horrid and unnatural Rebellion and War" had been raised against

the Commonwealth.

More info

The Massachusetts Senate and House of Representatives expressed in a letter to the governor their "entire satisfaction in the measures You have been pleased to take, pursuant to the powers vested in You by the constitution for the subduing a turbulent spirit, which has too long insulted the Government of this commonwealth, prostrated the courts of law and Justice in divers counties, and threatened even the overthrow of the constitution itself." One day after the Governor's address, the Massachusetts General Court issued a declaration that a "horrid and unnatural Rebellion and War, has been openly and traitorously raised and levied against this Commonwealth, and is still continued, and now exists within the same." Rufus King, the Massachusetts delegate to the United States Confederation Congress delivered copies of the governor's address and the legislature's response.(10)

As strongly as he felt that the insurgents must be stopped, Governor Bowdoin realized, like General Benjamin Lincoln, that there were not jails enough to hold all of those who had taken up arms against the state. He also believed that, once the leaders had been removed, the rank-and-file rebels would see the error of their ways. On February 16, 1787, his administration enacted the Disqualification Act. The act offered pardons to all but the leaders of the rebellion. All former insurgents had to do was come forward, surrender their arms, and swear an oath of allegiance to the state. In an attempt to forestall future unrest, the act forbade oath takers from holding public office, sitting on juries, voting, teaching, operating a tavern, or selling ardent spirits for three years. If these men proved to be law-abiding citizens loyal to their state and country, then all restrictions would be lifted. Those unwilling to seek pardons would be harshly prosecuted, and rewards were offered for the capture of Daniel Shays, Luke Day and other rebel leaders.

Benjamin Franklin was among those who expressed admiration for and approval of Governor Bowdoin's handling of the rebellion. Franklin, the president of Pennsylvania, wrote to Bowdoin to "congratulate your Excellency most cordially on the happy success attending the wise and vigourous measures taken for the suppression of that dangerous insurrection; and I pray most heartily for the future tranquility of the state which you so worthily and happily govern." Franklin also informed the governor that the Pennsylvania government planned to issue a proclamation adding to the reward already being offered for "apprehending several promoters of the rebellion in your state."

Not everyone was pleased with Governor's Bowdoin actions, however. Massachusetts voters expressed their unhappiness in the spring elections; John Hancock defeated Bowdoin's bid for re-election in a landslide. Governor Hancock immediately issued a proclamation extending a full pardon "to those who have been misled, and are not so flagrantly guilty" as the "wicked and designing men" who had led the insurrection. He also subsequently pardoned all of the rebel leaders, including Daniel Shays and Luke Day. Two men, however, were executed in Berkshire County for looting in the course of their insurgent activities.(11)

The turmoil and violence confirmed James Bowdoin's belief that a stronger federal government was necessary for greater internal stability in Massachusetts and the other states. In 1788, he attended the Massachusetts ratifying convention and voted to accept the United States Constitution.(12) Two years later, he died of tuberculosis. Bowdoin College in Maine was named in his honor.

About This Narrative

Note: All narratives about people are, to the extent possible, based on primary and secondary historical sources.

See Further Reading for a list of sources used in creating this narrative. For a discussion of issues related to telling people's stories on the site, see: Bringing History to Life: The People of Shays' Rebellion

| Print | Top of Page