People

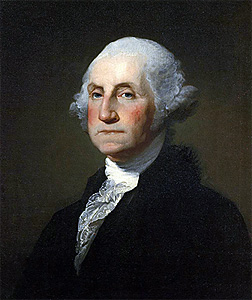

George Washington

1732-1799

George Washington

By Gilbert Stuart. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery, Washington DC

By 1786, General George Washington had enjoyed almost 3 years of retirement and hoped he had stepped out of the public eye for good. However, when news spread of an uprising in Massachusetts, Washington became concerned. Anxious for news, he relied heavily on reports from old comrades like General Henry Knox and General Benjamin Lincoln of Massachusetts. Similarly, Washington asked his former Continental Army aide, Colonel David Humphreys of Connecticut, to "write me fully, I beseech you, on these matters; not only with respect to facts, but as to opinions of their tendency and issue."

But for God's sake tell me what is the cause of all these commotions: do they proceed from licentiousness, British-influence disseminated by the tories, or real grievances which admit of redress? If the latter, why were they delayed 'till the public mind had become so much agitated? If the former why are not the powers of Government tried at once?(1)

Washington worried that "[c]ommotions of this sort, like snow-balls, gather strength as they roll, if there is no opposition in the way to divide and crumble them. I am mortified beyond expression that in the moment of our acknowledged independence we should by our conduct verify the predictions of our transatlantic foe, and render ourselves ridiculous and contemptible in the eyes of all Europe."(2)

In October 1786, Washington wrote to Henry Lee of Virginia expressing alarm at the news from the "Eastern States" and repeating his dismay at the impression the turmoil must make on other nations, including Great Britain.

the accounts which are published of the commotions…exhibit a melancholy proof of what our trans-Atlantic foe has predicted; and of another thing perhaps, which is still more to be regretted, and is yet more unaccountable, that mankind when left to themselves are unfit for their own Government. I am mortified beyond expression when I view the clouds that have spread over the brightest morn that ever dawned upon any Country… To be more exposed in the eyes of the world, and more contemptible than we already are, is hardly possible.(3)

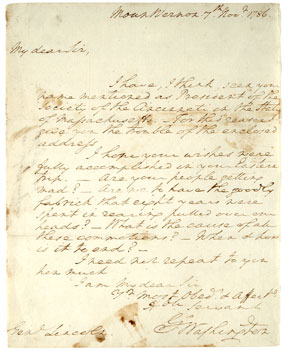

Letter to Benjamin Lincoln from George Washington asking for a report on Shays' Rebellion.

More info

As the news coming out of Massachusetts grew worse, Washington asked General Lincoln, "Are your people getting mad? Are we to have the goodly fabric that eight years were spent in raising pulled over our heads? What is the cause of all these commotions? When and how will they end?" Lincoln's response was hardly reassuring; "Many of them appear to be absolutely so [i.e., mad] if an attempt to annihilate our present constitution and dissolve the present government can be considered as evidence of insanity."(4)

It was with relief that Washington received the new from General Knox of the "success of General Lincoln's operations" against the insurgents:

On the prospect of the happy termination of this insurrection I sincerely congratulate you; hoping that good may result from the cloud of evils which threatned, not only the hemisphere of Massachusetts but by spreading its baneful influence, the tranquillity of the Union.(5)

The turmoil in Massachusetts that would later become known as Shays' Rebellion played a key role in convincing Washington to come out of retirement. By March 1787, General Knox felt confident that Washington would attend the convention scheduled to convene in Philadelphia that spring to revise and strengthen the existing Articles of Confederation. Washington's agreement to chair the Convention and endorse its efforts gave crucial legitimacy to the proposed United States Constitution, aiding in its adoption by all thirteen states, including Massachusetts.

Shays' Rebellion strengthened at a critical time the movement to create a stronger federal government. In doing so, it also ended George Washington's dream of a long and peaceful retirement from public life. Washington was unanimously elected to serve as the first President under the new Constitution. He served for two terms and at last retired to his estate at Mount Vernon, where he died in 1799.

About This Narrative

Note: All narratives about people are, to the extent possible, based on primary and secondary historical sources.

See Further Reading for a list of sources used in creating this narrative. For a discussion of issues related to telling people's stories on the site, see: Bringing History to Life: The People of Shays' Rebellion

| Print | Top of Page