People

Henry Knox

1755-1806

Henry Knox

By Charles Willson Peale, from life, c. 1784. Courtesy Independence National Historical Park, Philadelphia, PA

Prologue

A bookseller from Boston, Knox was only 25 years old when war broke out in 1775. A self-taught military strategist with a passion for artillery, Knox masterminded the transportation of cannons from Fort Ticonderoga in New York to Dorchester Heights above Boston in the winter of 1776. General George Washington quickly recognized Knox's talents and energy, and promoted him to Major General and Chief of Artillery. In 1778, Knox helped to establish the United States Arsenal at Springfield, Massachusetts. As the war drew to a close, Knox was instrumental in founding the Society of the Cincinnati, a hereditary order restricted to officers of the Continental Army and their descendants. Knox served as the Secretary of the War Department under the Articles of Confederation during Shays' Rebellion.(1)

General Henry Knox and General George Washington signed this diploma of membership in

the Society of the Cincinnati belonging to Colonel Hugh Maxwell of Charlemont, Massachusetts.

More info

Courtesy of Historic Deerfield, Inc.

"the fine theoretic government of Massachusetts has given way"

As the situation in Massachusetts deteriorated through the summer and fall of 1786, Henry Knox kept up a constant stream of communication with his former commander-in-chief. Knox described for Washington in apocalyptic terms the actions and motives of those taking up arms against the Massachusetts government. On October 23, 1786, he lamented that "[o]n the very first impression of faction and licentiousness, the fine theoretic government of Massachusetts has given way, and its laws [are] trampled underfoot." Knox dismissed the theory entertained by some observers from outside the state that heavy, aggressive taxation had caused the crisis. This notion, Knox informed Washington, was "a deception equal to any that has been hitherto entertained. That taxes may be the ostensible cause is true… but that they are the real cause is as far remote from truth as light from darkness." According to Knox, "[t]he people who are the insurgents have never paid any, or but very little taxes- But they see the weakness of government; They feel at once their own poverty, compared with the opulent, and their own force, and they are determined to make up the latter, in order to remedy the former." Like Rufus King, a Massachusetts representative to the United States Congress, Knox believed the true aim of the insurgents was to forcibly redistribute property from the wealthy to the less fortunate:

Their creed is, "That the property of the United States has been protected from confiscation of Britain by the joint exertions of all, and therefore ought to be the common property of all, and he that attempts opposition to this creed is an enemy to equity and justice, and ought to be swept from off the face of the earth." (2)

If this was not grounds enough for worry, Knox warned Washington that

Having proceeded to this length, for which they are now ripe, we shall have a formidable rebellion against reason, the principle of all government, and against the very name of liberty. This dreadful situation, for which our government have made no adequate provision, has alarmed every man of principle and property in New England. They start as from a dream, and ask what can have been the cause of our delusion? What is to give us security against the violence of lawless men? Our government must be braced, changed, or altered to secure our lives and property.(3)

Knox's dire reports and predictions confirmed Washington's worst fears that the survival of order and free government in Massachusetts hung in the balance. At the same time, the Secretary of the War Department was curiously unwilling to sanction the use of weapons and supplies belonging to the United States against the insurgents. When General William Shepard of Westfield wrote to Knox pleading with him to endorse his decision to arm local militia using guns and ammunition commandeered from the United States Arsenal at Springfield, Knox replied that he lacked authority to give that permission. That authority, Knox wrote, rested with the United States Congress, which was not currently in session. General Shepard decided to go ahead without this formal permission, declaring to Governor James Bowdoin that his unauthorized action was necessary lest the Arsenal "fall into into Enemies from too punctilious observance of Forms." Shepard's decision to fire the Arsenal artillery at an advancing column of 1,400 insurgents led by Captain Daniel Shays earned the gratitude of the state and the life-long enmity of his neighbors.(4)

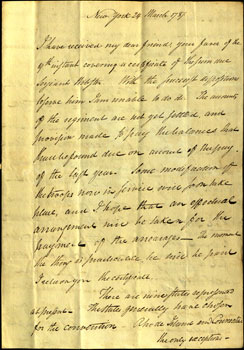

General Knox's calm and optimistic assessment of the insurgency in a letter to Colonel Jeremiah Wadsworth of Connecticut was a curious contrast to the grim, worst-case scenario reports Knox had been sending George Washington. Knox assured Wadsworth in March, 1787 that

The little predatory incursions of the insurgents of Massachusetts, are the last struggle of an expiring faction - If the Supreme Court act with vigor, and a few executions take place, the business of insurgency in Massachusetts will most probably be finished for the present.(5)

General Knox assured his friend Colonel Jeremiah Wadsworth in March 1787 that "a few

executions" would finish the insurgency.

More info

Courtesy of the Connecticut Historical Society

In the same letter, Knox complacently informed Wadsworth that Washington would likely attend the upcoming convention in Philadelphia called to revise and strengthen the Articles of Confederation. Knox did not add that the information he had been sending Washington had played an important part in the former commander-in-chief's decision to go to Philadelphia. Washington was elected president of the convention and threw his weight behind the proposed federal plan. Knox strongly supported the new United States Constitution, which included a clause empowering the United States Congress to "provide for calling forth the militia to execute the laws of the union, suppress insurrections and repel invasions."

Epilogue

When Washington was unanimously elected to serve as the first president under the new Constitution, he appointed General Henry Knox Secretary of War. In 1794, Henry Knox retired to his extensive holdings in Maine, where he died in 1806.

About This Narrative

Note: All narratives about people are, to the extent possible, based on primary and secondary historical sources.

See Further Reading for a list of sources used in creating this narrative. For a discussion of issues related to telling people's stories on the site, see: Bringing History to Life: The People of Shays' Rebellion

| Print | Top of Page