People

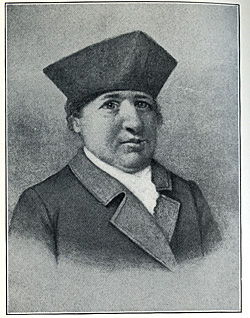

William Shepard

1737-1817

William Shepard

From Westfield and Its Historic Influences 1669-1919, by Reverend John H. Lockwood, D.D. Courtesy Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, MA

William Shepard was born in 1737 in Westfield, Massachusetts. War and military service would shape the course of Shepard's long life. Like many young Massachusetts men, 17-year-old William joined the Massachusetts militia and fought in the French and Indian War. Six feet tall and well-built, William Shepard turned out to be an excellent soldier and officer, earning several promotions before the war ended in 1763. In the 1770s, he embraced the Whig, or Patriot, cause. He was a member of the local Committee of Correspondence, and his military experience made him a logical choice to command militia as his community prepared for the possibility of war with England. Commissioned as a colonel in the 4th Massachusetts Regiment of the Continental Army in October 1776, he served through the entire war and fought in 22 engagements. Colonel Shepard's regiment saw action in New York, Trenton, Princeton, Saratoga, Monmouth, and Rhode Island. When the war ended, his regiment was among the last to be disbanded, in November 1783 at West Point, New York.(1)

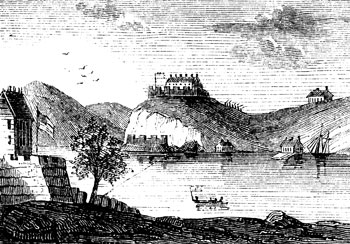

Colonel Shepard's 4th Massachusetts Regiment, was stationed at West Point, New York,

when it was disbanded on November 3, 1783.

More info

After the war, Colonel Shepard received a commission as a major general in the Massachusetts state militia. Later events proved showed the state's choice to have been a wise one. Shepard was typical of higher-ranking Continental Army veterans in his firm support of law and order.(2) He unhesitatingly cast his lot with the Friends of Government during the turbulent court closings in the summer and fall of 1786. In September, General Shepard commanded the government militia streaming into Springfield from surrounding towns to protect the Supreme Court from hundreds of other local men marching to close it.(3)

Springfield was the site of the United States Arsenal. Established during the American Revolution, the Arsenal and its stores of weapons, ammunition and other supplies were the property of the United States government. Although he lacked official authorization from the Confederation Congress to do so, Shepard issued his poorly-armed militia Arsenal muskets, and placed Arsenal cannon in front of the Courthouse. Angry shouts and taunts filled the air as Regulators determined to stop the court faced militia determined to defend it. Shepard met with Captain Daniel Shays of Pelham, who spoke on behalf of the Regulators. Shepard flatly refused to bow to any of Shays demands but agreed to allow the Regulators to parade around the courthouse.(4)

Shouts and taunts punctuated the confrontation between General Shepard's government

militia and Regulators led by Captain Daniel Shays.

General Shepard observed that many of Shays' men carried only sticks and staves. This fact convinced him that the Springfield Arsenal and its stores was a tempting target for the poorly-armed insurgents. In a letter to General Henry Knox, Shepard shared his concern that, should these men obtain Arsenal weapons, they would terrorize the state.

You will, Sir, for a moment consider, that the greater part of the insurgents will go from the Counties of Hampshire & Berkshire, and in their rout probably pass by these stores. If they are determined to carry their point, and subject the whole State to their lawless sway (which they boast is in their power) will they tamely pass by the very means which they want to effect their purpose, without making one serious effort?(5)

In a flurry of letters to General Knox, Governor James Bowdoin, and General Benjamin Lincoln Shepard urged that measures be taken to defend the Arsenal. That the government militia lacked weapons themselves added to the sense of crisis:

Half the Militia which will be in the field, for the defence of the public stores, will not have arms so good as clubs, and there is not a single piece of Artillery in this division. Must I, thus prepared with arms, hazard the safety of the stores, the defeat of my party, the disgrace which would fall on myself, and the security of the State, by a wicked Banditti of rebels? God forbid.(6)

Shepard was determined "to defend those stores to the last moment, unless they get possession of them, before I can raise my men and get it myself." As it turned out, Shepard won the race. Local militia under his command took possession of the Arsenal on January 18. Sleighloads of men and supplies continued to arrive over the next several days. (7) Writing to Governor Bowdoin on January 19, Shepard discussed his preparations for defending the Arsenal, including his decision to use its weapons "as it would be highly absurd that the Magazine should finally fall into Enemies from too punctilious observance of Forms."(8)

On the afternoon of January 25, 1787, about 1,400 of the men Shepard called "a wicked Banditti of rebels" advanced on the Arsenal, led by Captain Daniel Shays. Suffering from the bitter cold, the prospect of sheltering in the Arsenal barracks drew Shays' men as irresistibly as the weapons stored there. In their way stood 1,200 men from surrounding towns who had answered the government's call for militia to defend the Arsenal. General Lincoln was on the way from Boston with 4,000 more men, but they had not yet arrived. With or without Lincoln's militia, General Shepard had no intention of allowing Shays' men to take the Arsenal.

Determined as he was to defend his position "at all hazards," Shepard nevertheless tried to avoid bloodshed. He sent out an officer in hopes of convincing Shays to abandon his plan. When Shays and his men refused to disperse, Shepard ordered his artillery to fire warning shots above the heads of the advancing column. Only when the insurgents continued to march on did General Shepard give the fateful order to fire the cannon and howitzer directly into the approaching army "at waistband height." Under Major William Stevens' experienced command, the gun crews fired several rounds. Cannonballs and grapeshot ripped into the center of the column, killing three men instantly and wounding over twenty more. Shocked and horrified, the insurgents broke and fled.

Originally situated on the grounds of the Springfield Arsenal, this monument bears the

scars of the deadly artillery fire General Shepard ordered against the approaching column of

1,400 Regulators.

More info

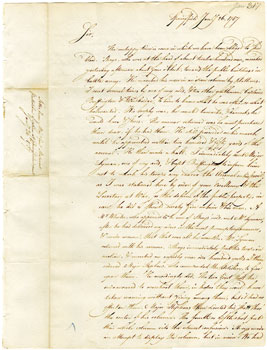

In a letter to Governor Bowdoin dated the following day, General Shepard lamented, "The unhappy time is come in which we have been obliged to shed blood." After describing "the utmost confusion" the artillery had produced in Shays' approaching column, Shepard hastened to assure the Governor that he had exercised restraint: "Had I been disposed to destroy them, I might have charged upon their rear & flanks with my Infantry & the two field pieces & could have killed the greater part of his whole army within twenty five minutes." Shepard's decision to use the artillery had prevented close fighting; he was glad to report that "[t]here was not a single musket fired on either side." Lest it appear he had fired upon a peaceable group, the General offered evidence that the rebels had come prepared to fight had they had been allowed to come within firing range; "[t]hree muskets were taken up with the dead, which were all deeply loaded." Lack of reinforcements contributed to Shepard's decision not to pursue the fleeing mob, but he remained alert for another anticipated assault. "I have received no reinforcement yet, & expect to be attacked this day by their whole force combined."(9)

General Shepard described his successful defense of the United States Arsenal

in this letter to Governor James

Bowdoin.

More info

General Lincoln arrived with his army of militia late the next day. Together, he and Shepard coordinated a night action across the frozen Connecticut River, routing insurgents under Captain Luke Day who had not joined the abortive Arsenal assault. Several days later, General Lincoln pursued the remnants of the Regulator army to Petersham, catching it entirely by surprise on the morning of February 4. Resistance crumbled; Shays and his officers fled over the border into New Hampshire and Vermont. Hundreds of insurgents were captured on the spot, while others fled what was clearly a lost cause.(10)

Commendations and Resentments

His actions on January 25, 1787 created a complicated legacy for Shepard. Lauded by the government for his "spirited defence" of the Arsenal, many of his neighbors found those same actions unforgiveable. In an undated letter written about 1790, Shepard complained that his decision to fire on Shays' men at the Arsenal had

excited against me the keenest Resentments of the disappointed Insurgents, manifested in the most pointed Injurys, such as burning my Fences, injuring my Woodlands, by Fire, beyond a Recovery for many Years – wantonly & cruelly butchering two valuable Horses, whose ears were cut off and Eyes bored out before they were killed ~ insulting me personally with the vile Epithet of the Murderer of my Brethren, and, through anonimous Letters, repeated by threatening me with the Destruction of my House and Family by Fire.- which kind of Injuries I occasionally experience even to this day.(11)

At the same time, Shepard's status as a community leader and a friend of government earned him the respect of those who appreciated his willingness to defend the state of Massachusetts "at all hazards." In addition to serving in numerous local, state and local offices, he was a deacon on the church. He presided over militia exercises and drills, where his presence and military bearing inspired admiration and respect: "When I recall his large, imposing figure, bedecked with his trusty sword and crimson sash…and heard the whispers 'there's the general,' I remember the awe, notwithstanding his genial face, with which he inspired me." In the years following the ratification of the new United States Constitution, Shepard emerged as a strong Federalist, serving in the United Stated Congress from 1797-1803. (12)

Epilogue

General Shepard spent his final years in reduced circumstances. He blamed his situation in part on having spent his own money raising troops and supplies to defend the state during Shays' Rebellion. Shepard's financial sacrifices included having had to sell off a certificate he had received in lieu of cash payment for his years of service in the Continental Army. Shepard experienced the same disadvantages as other veterans who needed to raise money quickly at a time when the government-issued certificates were not holding their value. He had been "obliged to dispose of a final Settlement Certificate of Eleven hundred and thirteen Dollars, at less than four Shillings on the pound to repay a part of the Money I borrowed before I received any from the Commonwealth." General Shepard died in 1837 at age 80, and was buried in the Mechanic Street Cemetery. Over time, pride in Shepard's Revolutionary War service overwhelmed the controversy his decisions at the Arsenal had generated during his lifetime. As part of the town's 250th celebration in 1919, Westfield erected a statue and celebrated Shepard as a hero of the Revolution. When Westfield decided in 1921 to adopt a town seal, the only stipulation the designer received was that it include an image of General William Shepard.(13)

About This Narrative

Note: All narratives about people are, to the extent possible, based on primary and secondary historical sources.

See Further Reading for a list of sources used in creating this narrative. For a discussion of issues related to telling people's stories on the site, see: Bringing History to Life: The People of Shays' Rebellion

| Print | Top of Page