People

Luke Day

1743-1801

Luke Day

© 2008 Bryant White

Prologue

On July 21, 1743, Luke Day, Jr., was born in Springfield, Massachusetts, the third child of seven born to Luke Day, Sr., and Jerusha Skinner. The Days were one of West Springfield, Massachusetts' most prominent families. Scarcely a year passed without a member of the Day family holding a town office. Luke's father's cousin, Benjamin Day, was well known as the town's first moderator, selectman, and town representative to the General Court. Another cousin, Josiah Day, owned the property that today serves as a museum and memorial to the family.

The Day House in West Springfield may have served as Luke Day's headquarters during Shays' Rebellion.

More info

Courtesy Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, MA

Luke, Jr., married Lydia Kelsey of Killingworth, Connecticut, on August 20, 1762, in Westfield, Massachusetts. Both were 19 years old. Over the next 17 years, Luke and Lydia had 8 children; 2 died in infancy, and another died at age 13. All of the remaining children—four sons and a daughter—survived to adulthood, and all five married. (1)

Call to Arms

When news reached West Springfield of the fighting at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, Luke marched to Boston with a local militia company. Luke was soon promoted to first lieutenant and, along with 1,100 other men, volunteered to take part in Benedict Arnold's epic, failed Quebec expedition in 1775. Luke was later promoted to Captain. He served in the Continental Army through the Revolution, although illness furloughed him at home for the most of the latter part of the war.

As Commander-in-Chief of the Continental army, George Washington had encouraged his officers to assume the marks of distinction and behavior that signaled their military and accompanying social status as gentlemen. This typically included officers wearing elegant dress, hiring servants, buying better food than what was issued to the common soldiers, and assuming the expenses of equipping and maintaining a horse. Luke resisted assuming this lifestyle, believing he would maintain better camaraderie with his soldiers if he retained habits more akin to theirs. Even though his family owned substantially more property than did the families of ordinary soldiers, he realized that living beyond what his infrequent pay could cover would only bring on financial woes for the future. Like other officers and enlisted men during the long war, Luke was paid infrequently or in notes that initially had little market value and then quickly depreciated. (2)

In the late spring of 1782, while on a medical leave at home, Luke helped put down an uprising against the Massachusetts wartime government. Known as "Ely's Rebellion," the movement was spearheaded by the Reverend Samuel Ely. Ely urged Massachusetts citizens to overthrow the new Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 and establish what he and his followers considered more representative republican government. As in the years leading up to the American Revolution, the courts and judges became targets for those protesting what they saw as government corruption and injustice. When a mob threatened the Court of Common Pleas at Northampton, Captain Day responded to the government's call for troops to protect the court. Luke and other soldiers successfully defended the judges by standing on the courthouse steps and defying the demands of the mob. (3)

In 1783, Luke joined the exclusive and newly-formed Society of the Cincinnati. Membership in this fraternal organization was open only to veteran officers of the Continental Army and their firstborn sons. One of the Society's goals was to lobby the governments to ensure that veteran Continental Army officers received half-pay pensions for life, as retired British officers did. Luke donated one month of his pay to join this organization, most likely hoping that in return, he would "rub shoulders with great men" and get preferential treatment from the state or national government after the war. (4) Society of Cincinnati members lobbied extensively for positions, land, and pensions. The Society was deluged almost immediately with angry criticism by those who condemned it as an aristocratic institution at odds with the egalitarian ideals of the new republics. Despite the promises by the Continental Congress to Luke and other commissioned officers, the policy was soon commuted to just five years' full payment to veteran officers of government securities bearing six percent interest. Worse, by the time the states approved the settlement in 1784, the notes had depreciated to about one-eighth of their face value. (5)

Following his official discharge in 1783, and in the face of rising state and local taxes, the farms belonging to Luke and his immediate family deteriorated. Before the war Luke's father was listed in the top five percent of town taxpayers. The demand for farm goods increased during the war. Unfortunately, with Luke and one of his brothers serving in the army, the family lacked the manpower to produce what the farms needed to in order to thrive. By the war's end the Day family paid in taxes four times what they had before the war and were no longer in the top five percent of town taxpayers.(6) Luke incurred more and more debt as he struggled to resuscitate his deteriorating farm and pay the tax collector. By 1785 Luke was in debtor's prison in Northampton. (7) Like other imprisoned debtors, Luke was permitted to leave the jail during the day as long as he stayed within certain set boundaries and returned each night. After two frustrating months, Luke "broke his bond" by leaving Northampton and heading home to his farm and family.

Disrupting the Courts

In the months that followed, Luke met with local people to discuss their financial plight and their anger with the government that seemed so obstinately opposed to serving the people. Many of them, like Luke, believed that scripture as well as natural rights justified, even demanded, the active resistance they contemplated. It is said that Luke believed God might speak directly to him through the Bible, and that he discovered a passage in Ecclesiastes (4:1) that seemed to speak directly to the times: "Behold the tears of such were oppressed, and they had no comforter; and on the side of the oppressor there was power." (8) That summer, a number of residents attended a convention in Hatfield, Massachusetts, where they voiced their grievances and demanded radical changes to the state government, including the creation of a new state constitution.

Towns unhappy with Massachusetts government policies sent delegates to county conventions such as the one illustrated here in an engraving from Bickerstaff's Boston Almanack for 1787.

More info

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA

On the morning of August 29, 1786, just six days after the Hatfield Convention, groups of men from surrounding towns began making their way toward Northampton, where the quarterly session of the Court of Common Pleas was scheduled to open that day. Luke and a body of men from West Springfield joined the hundreds converging on the town. Sheriff Elisha Porter of Hadley recognized many of the men who entered town to the music of fifes and drums. By noon there were 500 armed men. Those without swords or muskets wielded hickory clubs. Alarmed residents shuttered themselves in their shops and houses.

Sheriff Porter led the judges from Clark's Tavern, where they had put on their gray wigs and black gowns. Luke Day, who just a few years before had defended the court, now insisted it not open. While his men surrounded the approach to the courthouse, Captain Day stood on the steps with a petition in his hand for the judges. The petition stated that it was "inconvenient" to the people of the state for the courts to sit that day, and entreated the judges to adjourn until the petitions of the conventions might be granted by the General Court. By the time the judges retreated to the tavern to consider the petition, the crowd of men had grown to 1500. (9) The justices decided to "continue all matters pending" until November and "adjourned without delay." (10)

Captain Luke Day stood on the courthouse steps with a petition in his hand for the judges at this Northampton Courthouse on August 29, 1786.

More info

Courtesy Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, MA

During the fall of 1786, Luke Day and Daniel Shays of Pelham became the most conspicuous and authoritative leaders of the insurgents in Hampshire County. Both spent time on the West Springfield common organizing and drilling militia who referred to themselves as "Regulators." They also met and discussed their plans and opinions in taverns and other public spaces. Although he lacked a formal education, Luke was said to be a practical, intelligent, persistent and popular leader. As he looked over the crowd of Regulators, armed with hickory clubs and distinguished by hemlock sprigs—signifying liberty—tucked into their hatbands, he must have felt some pride realizing that among the West Springfield crowd were 26 of his relatives. (11)

Of the men who were gaining attention as prominent Regulators, it was Daniel Shays rather than Luke Day who became identified as the main leader of the movement that would bear his name—although Luke's stature in the community and his extensive kinship connection may have made him the better choice. Later comparisons of Day and Shays published in a 1926 history of Springfield suggested that it was as much chance as intent that resulted in Shays assuming a leadership role in the Regulation:

It was more the result of accident than any other cause that Shays had the precedence, and the fortune to make his name infamous by association with the rebellion in which he was engaged. Day was the stronger man, in mind and will, the equal of Shays in military skill, and his superior in the gift of speech. (12)

Yet, other accounts emphasized the distrust some felt for Luke's emotionally outspoken religious sentiments, his tendency to draw too much inspiration from the Bible for the job at hand. It was feared that a time would come when he would rely too heavily upon divine guidance and become more of a dictator and less of a democratic leader.

Governor Bowdoin feared the protestors might disrupt the Supreme Judicial Court scheduled to meet in Springfield in September. He therefore ordered out the militia from nearby towns under General William Shepard. Although the judges, protected by the militia, managed to convene the court, hundreds of Regulators led by Shays succeeded in preventing them from transacting business. Once the Court had closed, Shepard withdrew the government militia and began preparing to defend the United States Arsenal located in Springfield.

As in 1774, thousands of Massachusetts men marched on Springfield to shut down a court session they believed betrayed the principals of free government. Detail from Petition & Protest

© 2008 Bryant White

In late October, the state cracked down on the Regulation, issuing the Militia Act and the Riot Act. In addition, the Legislature soon suspended the Writ of Habeas Corpus, thus allowing suspects to be imprisoned anywhere in the Commonwealth without the right to challenge their imprisonment.

Like many other Massachusetts citizens, Luke Day and Daniel Shays were shocked by the suspension of Habeas Corpus and the accompanying revocation of ancient English liberties they had fought to preserve in the War for Independence. Thousands of armed protesters, including veterans of the state militia and Continental Army, continued seeking reform through regulating the government and its leaders, including judges and courts. In the next months, the Regulators marched on Worcester and Concord.

On December 26th, 1786, Shays appeared in Springfield on a white horse, leading a well-armed, well-drilled company of 300 men, including Luke Day. They took possession of the Courthouse and petitioned the Supreme Judicial Court not to open. The judges did open the court, but complied with the request to adjourn without doing any business.

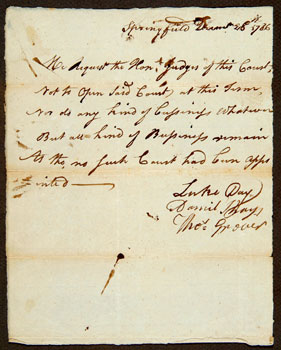

Luke Day handed this petition to judges at the Springfield Court on Dec. 26th, 1786.

More info

Courtesy Pennsylvania Historical Society, Philadelphia, PA

By January 10, 1887, with another court due to convene in Worcester in 10 days, Governor Bowdoin responded to fears that the men the government called "insurgents" would again try to interfere. He issued warrants to the Sheriff of Hampshire County for the arrest of the ringleaders. Realizing that the conflict was escalating, and in need of arms and equipment, the insurgents turned their eyes toward the barracks and stores of the United States Arsenal at Springfield.

A Failure to Communicate

On January 15th, Shays and his leaders dispatched orders to officers throughout Hampshire County to muster their respective commands, fully armed and equipped, with 10 days' rations, to rendezvous in Pelham by January 19th. The rebels were divided into three regiments, each under the command of a former Revolutionary War officer with five or more years of experience, but miles apart in three different Massachusetts towns. Daniel Shays gathered his forces in Palmer; Eli Parsons collected his troops in Chicopee; and Luke Day assembled his men across the Connecticut River in West Springfield. Since they were not in close proximity, each would have to rely upon messengers for communication.

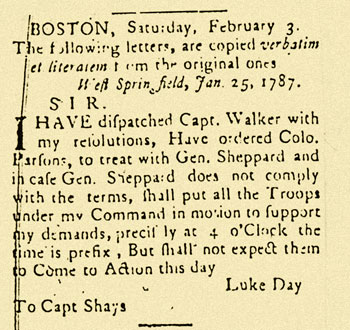

Just before a three-pronged attack planned for January 25th, Luke Day unilaterally decided to change the plan. Claiming to represent the "body of the people assembled in arms," he sent an ultimatum to General Shepard, giving him and his forces 24 hours to lay down their arms and return home. He declared that if they did not do so, he would "give nor take no quarter." At the same time, Luke sent a message to the other two commanders informing them of the postponement of the attack until January 26th. However, the message was intercepted by Shepard's men; Day's change of plan never reached Shays and Parsons.

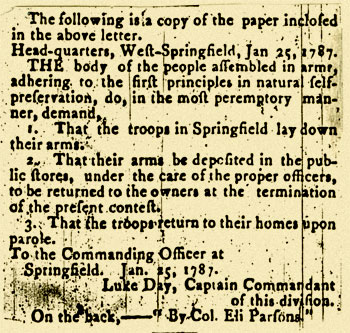

The Hampshire Gazette printed this copy of the ultimatum Luke Day originally sent to General Shepard on January 25, 1787.

More info

Courtesy Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, MA

The Hampshire Gazette later printed this copy of the letter Luke Day sent to Shays and Parsons on January 25, 1787, telling them of his change of plans.

More info

Courtesy Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, MA

Why did Luke Day change the plan? Some historians believe that Luke's unreadiness to march until January 26th explains the delay; others suggest that Day wanted to give Shepard a 24-hour warning. An unsubstantiated story offers a third possibility. According to this anecdote, on the eve of the arsenal attack, the pastor of the First Church of West Springfield, Joseph Lathrop, tried to convince Luke to stand down. The minister, a strong government supporter and an influential local figure, allegedly told Day that "his army was 'deficient of good, true and trusty officers,' that he was 'engaged in a bad cause' and his men knew it, and that he ought to 'disband them, and let them return peaceably to their homes; for as sure as you advance upon the public stores, tis as certain that you will meet with sure defeat.'" (13). If this story is true, it could explain Luke's reluctance to march and hence his change of plan.

Joseph Lathrop

Courtesy Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, MA

One can only imagine what Luke Day thought when word reached him that the march on the Arsenal had already taken place without his regiment. Eli Parsons, who had marched from Chicopee, blamed Day for botching the original plan.

Rout and Escape

On January 27th, General Shepard moved his forces against Shays on the east side of the Connecticut River. Shepard was reinforced by General Benjamin Lincoln who arrived with 2,000 additional government militia to reinforce Shepard. In the early hours of January 28th, he led four regiments and four fieldpieces across the iced-over Connecticut River to "overawe" Day's forces and "frighten him to submission without bloodshed." (14)

Luke Day and his men scattered. Day led some men up the river to Northampton where they crossed into Amherst, and then followed Daniel Shays to Pelham. On February 4th, a number of the Shays forces were captured in Petersham, while the remainder fled. By the end of the month armed resistance had been crushed. Most of the Regulators, except for Shays, Day, and a few other leaders, were coming forward to take an oath of allegiance and surrender their weapons in exchange for a government pardon. Meanwhile, the General Court met and declared that a state of rebellion existed in the Commonwealth. A price was put on the heads of the most notorious Regulator leaders: $750 for Daniel Shays; $500 each for Luke Day, Adam Wheeler and Eli Parsons. (15)

Meanwhile, Shays, Day, and others escaped through Athol to Warwick, Massachusetts. On February 5th, they crossed the state line into Winchester, New Hampshire. From there, Luke crossed into Vermont to stay with a relative in Marlborough.

Epilogue

Luke Day was captured at Westmoreland, New Hampshire, sometime in February, 1787, and imprisoned in Boston. He was released and granted a free pardon on March 22, 1788, after the town of West Springfield sent a petition to the legislature requesting clemency. In it, they stated that "he was reluctantly drawn into the rebellion and would have desisted from his violent measure at an early period had he not apprehended danger from the party with which he was unfortunately connected." (16)

In July of 1787, the Society of the Cincinnati banished Luke Day for his part in what had become known as Shays' Rebellion. Between 1787-1793, he was sued at various times for failure to pay his mortgage. He began selling land to his pay debts. In 1791 his father died, but Luke was not mentioned in the will. Luke died at the age of 58 on June 1, 1801, at his home in West Springfield. According to a contemporary, he was poor and in pain from gout. (17) He was buried in an unmarked grave next to his parents, at the Paucatuck Cemetery in West Springfield.

About This Narrative

Note: All narratives about people are, to the extent possible, based on primary and secondary historical sources.

See Further Reading for a list of sources used in creating this narrative. For a discussion of issues related to telling people's stories on the site, see: Bringing History to Life: The People of Shays' Rebellion

| Print | Top of Page