Historic Scenes

Prologue: A Revolutionary People

Elihu Ashley, © 2008 Bryant White.

In August, 1774, Jonathan Ashley of Deerfield set out for Springfield, Massachusetts, to attend the Court of Commons Pleas, the colony’s lower judicial court. From the moment the young attorney left Deerfield, his brother Elihu began to worry. All day, Elihu moved restlessly through the town, calling on acquaintances and checking in at local taverns for any news of the court. His fears were confirmed that evening when a shaken Jonathan Ashley returned home. He reported that 1,500 angry men had surrounded the courthouse. Armed with clubs and staves, they had forced the judges, lawyers and court officers to swear they would not open the session. Moses Harvey from nearby Montague had been among “the mobb.” Known for his quick temper and bellicose disposition, Harvey had “much abused” Seth Catlin, a Justice of the Peace from Deerfield. As for Jonathan himself, Elihu wrote that he had never seen a person “so altered in my Life than my brother was. Entirely without Law, every Man left to the Mercy of his Fellow.” [1]

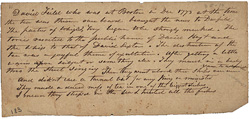

News of Boston's "tea party" in this "Tea Party Report" electrified the western Massachusetts town of Deerfield. Local divisions intensified as Whigs celebrated the destruction of the tea and Tories condemned the act. Courtesy of the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, MA.

The disorder and fear Jonathan Ashley experienced at the Springfield courthouse that August morning was not an isolated incident. It was but one of many episodes in which Americans confronted one another against the backdrop of rapidly deteriorating relations between Great Britain and its North American colonies. In western Massachusetts as elsewhere, families and communities fractured under rising political pressure and conflict as the British government tightened up oversight and administration of its colonies following the successful conclusion of the French and Indian War . When Whigs in Deerfield brought in a 45-foot liberty pole, their Loyalist neighbors promptly cut the pole in half. Mobs gathered outside the homes of suspected Loyalists while others assembled to protect the besieged. Liberty men celebrated the dumping of the tea in Boston Harbor, while the more conservative condemned the destruction of property and mourned the breakdown of law and order. In an attempt to quell future unrest and in reaction to the “tea party,” the British Parliament passed the Massachusetts Government Act, forbidding any but annual town meetings, and handing control of the judiciary over to the colony’s Royal Governor . [2]

Sketch of the 1770 New York liberty pole. More Info Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

Widespread, organized resistance to the Government Act erupted across Massachusetts. Angry and alarmed lawyers and court officials watched helplessly as Moses Harvey and thousands of other “Liberty Men” forcibly closed judicial courts in Worcester, Great Barrington and Springfield, all in the name of “the people.” A Massachusetts Provincial Congress formed a shadow government, citing the “intolerable grievances and oppression to which the people are subjected…manifestly designed to abridge this people of their rights…and, if carried into execution, will reduce them to a state of slavery.” As the debates over what seemed to be irreconcilable differences escalated, militias began drilling on town training fields, prepared to fight for the rights and liberties of the people, that more and more Americans believed would need to be defended by force. [3]

Twelve years and a revolution later, Seth Catlin faced Moses Harvey and the other men he still called “the mob” at Springfield, as thousands of Massachusetts men again marched against the judicial courts of Massachusetts. As in 1774, the protesters claimed to represent the “the body of the people” on whose behalf they were determined to close the courts “for their own good and that of the Commonwealth.” [4] The newly-created Massachusetts republic hovered on the brink of civil war as citizens on either side asserted their right to protect the liberties so dearly won in the Revolution.

[1] Amelia Miller and A.R. Riggs, eds., Romance, Remedies, and Revolution : the Journal of Dr. Elihu Ashley of Deerfield, Massachusetts, 1773-1775 (Amherst : University of Massachusetts Press ; Deerfield [Mass.] : Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, 2007), 112.

[2] An act for the better regulating the government of the province of the Massachuset’s Bay, in New England, 20 May 1774. A complete transcription of the act is available as part of the Avalon Project at Yale Law School at http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/amerrev/parliament/mass_gov_act.htm.

[3] William Lincoln, ed., The Journals of Each Provincial Congress in Massachusetts in 1774 and 1775, and of the Committee of Safety (Boston: Dutton and Wentworth, 1838), 18; Ibid., 72.

[4] Petition presented to the Court of Common Pleas at Worcester, 5 September 1786, quoted in Sidney Kaplan, Shays’ Rebellion, unpublished manuscript.