People

Elizabeth Porter Phelps

1747-1817

We are unaware of any surviving portrait of Elizabeth Phelps

Prologue

Elizabeth Porter Phelps was born in 1747 in Hadley, Massachusetts. Elizabeth was five years old when her father Moses Porter moved his wife, daughter and mother-in-law into a new home two miles from the main street in Hadley. He named his fashionable new home and estate Forty Acres. It was in this house that Elizabeth grew up, married and lived until her death in 1817.(1)

Named for her mother, Elizabeth grew up conscious of the prominent position her family held in the community and region. At a time when social prominence and political authority were two sides of the same coin, it is not surprising that Elizabeth's father was the Captain of the Hadley militia. Riding at the head of his company, Captain Porter and his men joined a regiment of militia headed to Crown Point, New York, during the French and Indian War. On September 8, 1755, Elizabeth's father was killed in action at Lake George during an engagement known as the "Bloody Morning Scout." Moses Porter was buried where he fell; only his sword came back to Forty Acres. Elizabeth's mother never recovered from this tragedy. She did not remarry. Plagued by illness and depression, she became addicted to the opium her physician prescribed for her. (2)

For all its outward prosperity, Forty Acres must have been a sad and lonely place for little Elizabeth. As her mother's emotional and physical health continued to deteriorate, her daughter shouldered more and more of the day-to-day management of the household. Eight years after her father's death, Elizabeth began keeping a regular journal. Her diary and surviving correspondence offer a remarkable record of a woman's spiritual life, work, family and community from the 1760s into the early decades of the new nation.(3)

Elizabeth was in her early twenties when Charles Phelps, also of Hadley, proposed to her. A few years older than Elizabeth, Charles did not initially meet with the Porter family's approval. His family was well-off, but socially inferior. The Porters could count themselves among the "River God" families that dominated the social, political and economic landscape of the Connecticut River Valley.(4) In contrast, Charles' father, Charles Phelps senior, was a bricklayer and mason who had become an attorney in his thirties. In a society based on social standing and hierarchy, his humble origins did not impress Elizabeth's family. Elizabeth's uncle Eleazer Porter was one of eleven Justices of the Peace for Hampshire County who resigned in protest when Governor Shirley appointed Charles' father to that office in 1759. The outraged Justices complained that Charles Phelps, Sr., was a man whose "company they never intended to keep." Thirteen years old at the time, young Charles was old enough to understand and resent his father's treatment.(5)

For her part, the objections of her family did not deter Elizabeth from encouraging Charles in his suit. On June 14, 1770 "at a few minutes before 4 oclock I gave my hand to Charles Phelps." At a time when wedding dresses were neither one-event garments nor universally white, the bride wore a dark brown silk gown. Her cousin and one of the groom's sisters attended as "Bride maids."(6)

Her family's initial misgivings were unfounded. Charles proved a good husband and provider, belying fears that he would squander the estate left to Elizabeth by her father. On the contrary, Charles was hardworking and astute. He soon began purchasing parcels of land, adding to the already-extensive holdings Moses Porter had acquired before his death. (7)

As members of a prosperous and prominent family, Elizabeth and her husband were expected to behave in a manner reflecting their elevated status. The couple several times updated as well as added on to their substantial home. An accomplished cheese woman, Elizabeth worked hard in the dairy, but held frequent tea parties in the afternoon. Regular in her attendance at weekly meeting, Elizabeth made a public profession of her conversion experience and became a full member of the Hadley church. Elizabeth was frequently called upon to assist less fortunate members of the community by providing housing, economic assistance and medical care. Dozens of hired men and women and indentured servants worked at Forty Acres. That the Phelps owned three slaves was another mark of status. Few people, Elizabeth included, questioned the existence of what would become after the American Revolution a "peculiar institution" at odds with American ideals of individual freedom and self determination.(8)

Cruelty and oppression

In the 1770s, both the Porters and the Phelps families were strong Whigs, supporting resistance to British colonial policies they believed to be tyrannical. Elizabeth's diary leaves no doubt as to her personal political beliefs. On June 19, 1774, she expressed outrage over Britain's closing of the port of Boston as punishment for the Boston Tea Party:

The People of this Land are greatly threatened with Cruelty and oppression from the Parliament of Great Britain—the Port of Boston is now and has been since the first day of this month shut up and greater Callamities [sic] are Daily expected.(9)

Throughout Massachusetts, people were on tenterhooks, expecting at any moment to hear of violence. Hadley joined other towns in declaring a public day of fasting. When Charles traveled to Springfield to sit on a grand jury at the Court of Common Pleas, he returned with news of a frightening altercation. Bells had summoned a mob of thousands to prevent the court from sitting. Elizabeth reported that a rumored invasion by the British army into the countryside around Boston rallied "vast numbers" of men "from all parts." When armed conflict at last broke out at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, Elizabeth considered it "a Civil war" and dreaded "all the Horrors of it."(10)

Hadley and other Massachusetts towns had been gathering ammunition and preparing for

war long before fighting broke out at Lexington and Concord in April, 1775.

More info

Forty-six Hadley men responded to the Lexington alarm. Elizabeth was overjoyed when in March, 1776, "the Regulars Left Boston which they have held as their Garrison this year…Glory to God." General Burgoyne's invasion of New England caused new alarm that ended in intense relief at the news of his defeat at Saratoga, New York, in 1777: "Oh wonderful, wonderfull Words cant express our adoration and Praise!"(11)

Mobs and Bloodshed

The war had moved out of New England, but fears of violence closer to home resurfaced. As they had on the eve of the war, thousands gathered to close down the courts of justice. The Massachusetts government, operating under the newly-ratified state constitution, hastily called up the militia. Elizabeth prayed fervently that the mobs led by Samuel Ely would disperse and that violence would be averted. Ely's arrest and imprisonment enraged his supporters, but the Elizabeth's cousin, Elisha Porter, managed to bring the affair to a peaceful conclusion.(12)

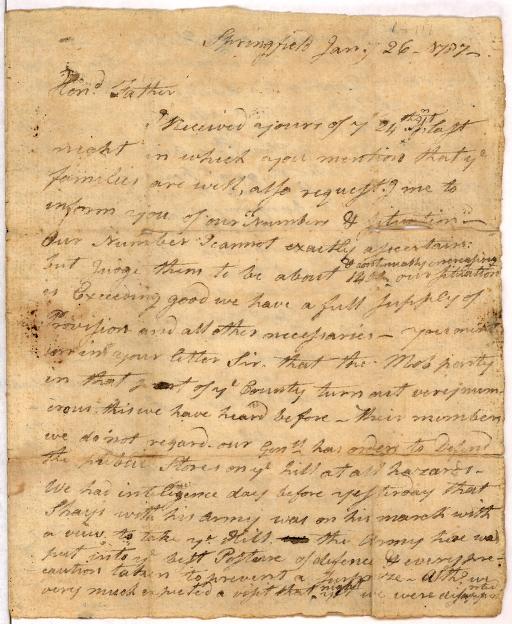

The end of the war in 1783 was a time of optimism and prosperity. Elizabeth's diary, however, revealed her concerns for her elderly mother, whose health was even worse than usual, in addition to battling depression so severe she could not get out of bed. In any case, the post-war prosperity was short-lived. By the fall of 1786, Elizabeth was once more writing anxiously of gathering mobs, courthouse closings, and the movements of government militia. In common with most of her Hadley neighbors, Elizabeth did not support the Massachusetts Regulators who were taking up arms against the state. Like other members of the local elite, the Porters and the Phelpses had supported the Revolution, but they also shared in common with other "friends of government" fears of disorderly mobs and the breakdown of law and order. Her husband had strong ties to the government. In contrast to her strong political views and statements during the war, however, Elizabeth did not condemn outright those involved in the protests. On hearing of that thousands of men were converging on the Supreme Judicial Court either to support it or to uphold, she expressed dismay that "publick affairs seem to be in a confused situation" and prayed that God would "bring order out of disorder."

When her husband went to Springfield in 1786, Elizabeth prayed for his safety and that

God would bring order out of disorder.

Elizabeth's hopes for a peaceful resolution dimmed as it became clear that neither the government nor the insurgents were going to back down. On January 14, 1787, Charles transported sleigh loads of men and supplies to the militia gathering to defend the United States Arsenal at Springfield. Meanwhile, Regulator regiments gathered under Captains Luke Day, Eli Parsons and Daniel Shays.

it looks Dark as Night, a very great Army is coming from Boston and some are Collecting on the other side. It appears as if nothing but the immediate interposition of providence could prevent blood.(13)

Elizabeth's fears were well-founded. Eleven days later, General William Shepard of Westfield ordered his artillery to open fire when the advancing insurgents ignored the initial warning shots. Several rounds later, three insurgents lay dead. Another, grievously hurt, died almost immediately. Twenty more were wounded. The victory belonged to the militia, but even there relief was mixed with the news that John Chaloner, a young man from Greenfield, was horribly maimed when he stepped in front of one of the cannon just as it went off.(14)

The "very great Army" of government militia, commanded by General Benjamin Lincoln, arrived at Springfield two days later. Shays' army fled through nearby Amherst to Pelham, and General Lincoln established his base at Hadley. When Shays' army retreated again to Petersham, General Lincoln ordered his army to pursue them. Making a forced night march in the teeth of a howling snowstorm, Lincoln's army completely routed the insurgents on February 3 at Petersham. In the days following, Charles Phelps once again delivered food and supplies to the government militia. Later that month, government troops clashed with insurgents at Sheffield, the last major conflict in what quickly became known as Shays' Rebellion.(15)

For Elizabeth, the lines were less clearly drawn than they had been during the Revolution. She referred to the times as "confused" and likely experienced a sense of relief as the violence and threat of civil war subsided during the spring and summer of 1788.

Epilogue

Elizabeth and her family continued to prosper in the decades following Shays' Rebellion. Her husband remained active in town affair and was appointed a Justice of the Peace in 1792. Between 1791and 1808, he represented Hadley for several terms in the Massachusetts General Court. Like her husband, Elizabeth was a strong Federalist and strongly opposed the policies of President James Madison, in particular the War of 1812. Two of Elizabeth's three children survived to adulthood, married, and made her a grandmother several times over. After 44 years of marriage, Charles Phelps died in 1814. Elizabeth Porter Phelps continued to write regularly in her journal until shortly before her death on November 11, 1817, just short of what would have been her 70th birthday.(16)

About This Narrative

Note: All narratives about people are, to the extent possible, based on primary and secondary historical sources.

See Further Reading for a list of sources used in creating this narrative. For a discussion of issues related to telling people's stories on the site, see: Bringing History to Life: The People of Shays' Rebellion

| Print | Top of Page