People

Hugh McClellan

1743-1816

Hugh McClelland

© 2008 Bryant White

Prologue

Six-year-old Hugh McClellan, or McClallen,(1) emigrated with his family from Ireland to Britain's Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1749. Shortly after arriving, Hugh's father bought land in Colrain and built a simple log house. The continual threat of raids on this isolated northern community by Native warriors from Canada convinced him to leave his property and move south and east to the town of Pelham in 1753. Michael McClellan died in Pelham in 1757. As the eldest son, (with five older sisters) young Hugh became the head of the household, responsible for keeping the family together and caring for their needs.(2)

Described as a tall, sturdily-built man with red hair and a ruddy complexion, Hugh moved his family back to Colrain, Massachusetts, in 1767. Like Pelham, Colrain had been settled mainly by Irish protestant families such as the McClellans seeking cheap land and an escape from ethnic persecution. Although Colrain was almost 30 miles away, the two towns shared a minister, and there was frequent intermarriage.(3) In Hugh's case, he married closer to home, choosing to wed Sarah Wilson of Colrain. A carpenter and a surveyor as well as a farmer, McClellan began building a frame house. Hugh and Sarah married in December of 1768. Their first child, Robert, was born the following year. Between 1771 and 1787, Hugh and Sarah had 7 more sons and 3 daughters. They lost two children: David, who lived less than 2 months, and Hugh, who died at the age of two.(4)

Hugh McClellan was an active member of the community, including serving as a town selectman. On the eve of the American Revolution, McClellan also served on the town's Committee of Safety and Correspondence. By 1775, he was Captain McClellan, drilling a minuteman company. Community status and popularity were important factors in selecting town militia officers. That 26-year-old Hugh was chosen suggests that he already had gained the trust and respect of his community. Captain McClellan's company of forty-four militia men was one of two minutemen companies from Colrain who marched to Cambridge upon receiving news of the fighting at Lexington and Concord. When 5,000 British and Hessian soldiers commanded by General John Burgoyne invaded the United States from Canada, Hugh McClellan was among the hundreds of western Massachusetts militia who flocked to stop them. Hugh fought in the Saratoga campaign at Bennington, Vermont, and at the battle of Stillwater, New York.(5)

Hugh McClellan participated in the remarkable defeat of Burgoyne's army at Saratoga in

1777. One of the men in his company picked up this British musket from the battlefield.

More info

Taxation Without Representation?

During the war, in addition to serving in the militia, Hugh also represented Colrain at the Massachusetts General Court, or State Legislature. Traveling over 90 miles to Boston on horseback, he would stay for several weeks while the legislature was in session. For poorer towns like Colrain, sending representatives was a financial and logistical challenge. In 1779, McClellan had not only the responsibility of his wife and 5 children, ranging in age from 10 years old to newborn, but also his widowed mother and siblings. It was a hardship for men like McClellan to spend weeks at a time away from family, farms and businesses without being paid for that service. There were occasions when Colrain could not afford to send McClellan to Boston, even when the General Court took on the responsibility of paying travel expenses for its members in 1780.

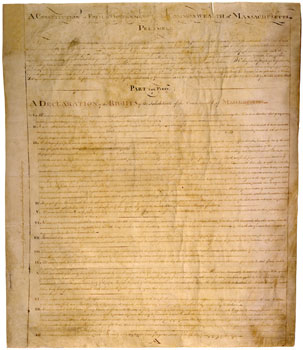

The winter of 1779 was particularly harsh, even by the standards of the severe weather patterns of the period, which were part of a longer cycle modern climatologists refer to as the Little Ice Age. During that winter, the Massachusetts Legislature called upon towns across the Commonwealth to send representatives to a convention in Boston to frame a new state constitution. Boston Harbor was frozen solid; most roads were impassable except by snow shoes. In the end, only 47 towns were represented at the convention, most from the eastern part of the state. This would bear bitter fruit when towns were asked to ratify the constitution the convention had created. Largely the work of John Adams, it remains the oldest, continually operating democratic constitution in the world. At the time, however, controversy swirled around the way in which it was ratified. Towns were encouraged to list their objections, article by article. If more than two thirds of the towns disapproved of the constitution, the convention was to make appropriate revisions to the document.(6)

Hugh McClellan served on the Colrain committee that reviewed the proposed constitution. Members advised that the 2nd Article include language that restricted office holding to loyal Americans: "no person be suffered to hold any office in the Commonwealth who has not been friendly to the independence of said Commonwealth." Not surprisingly, given the economic condition of most of Colrain's residents, the committee also rejected the constitutional requirement that citizens meet minimum property qualifications before they could vote, declaring, "Taxation without Representation we consider Unreasonable." As for a clause limiting elected office to men who met certain property requirements, Hugh and the rest of committee flatly stated that "we Consider money no Qualification in this Matter."(7)

Hugh McClellan and other Colrain citizens criticized the proposed

Massachusetts constitution for permitting "Taxation without Representation."

More info

The convention paid little or no attention to Colrain's objections or the concerns expressed by other communities. As it turned out, the system of piecemeal, article-by-article review by each town virtually ensured ratification without revision. It was practically impossible to compare town votes and sentiments on the individual aspects of the document, especially as towns often did not agree on the reasons for their concerns. The convention was able to report that the towns had approved every individual article of the constitution by a two thirds majority, ratifying on June 15, 1780.(8)

The following year, in 1781, the McClellan home burned to the ground. Hugh replaced it with a new, frame house. That same year he was appointed Colonel in the Massachusetts militia. In 1782, he became a Justice of the Peace, a position he would hold for the rest of his life.(9)

Choosing Sides

In the wake of the ill will generated during the ratification of the new state constitution, choosing whether to support the Massachusetts government or to join those protesting its policies was not always an easy decision to make. In company with other people in Hampshire County(10), Colrain residents hoped that by stopping the judicial courts from convening, they could protect poor but honest debtors from prosecution and the irretrievable loss of their property. In an incident that was part of the so-called Ely's Rebellion Colrain voted in April 1782 that no county court should prosecute cases for debt until the state government had responded to the grievances of the people. Hugh McClellan served on a committee that petitioned the General Court to postpone for the present all general sessions of the peace.(11) McClellan, luckily, was not in financial trouble himself. Nevertheless, he believed that debtors' grievances should be addressed before court action was taken against them.(12)

Four years later, the economic situation was even worse. The war had ended, only to be followed by a severe recession. As in other towns, these were hard times for Colrain. Already poor, the town could not pay the crippling taxes the Massachusetts Legislature had levied to pay the state's heavy war debts. Desperate and angry, many Colrain men took up arms, demanding debtor relief and constitutional reforms. The Massachusetts government called them insurgents, but the men and their supporters referred to themselves as Regulators. In August, armed with muskets and clubs, Colrain Regulators joined hundreds of other protesters from western Massachusetts. As in 1782, their destination was the Northampton Court of Common Pleas. With Captain Luke Day of West Springfield at their head, they closed the Court.

This time, however, McClellan did not side with his neighbors, most of whom supported the Regulation. Although he still sympathized with their plight and their grievances against the state government, he had decided that the evils of taking up arms against the state outweighed the benefits of using force to gain relief and reform. It could not have been an easy choice to make; Colrain supplied more Regulators than any town in Massachusetts.(13) Nevertheless, Colonel Hugh McClellan led a regiment of Hampshire County men to defend the Supreme Court at Springfield from the insurgents in September, 1786. Nor did illness prevent McClellan from defending the barracks and stores of the Unites States Arsenal at Springfield. The bloody encounter at the Arsenal on January 25, 1787 left four Regulators dead and over 20 more wounded.

Feeling betrayed by a man they had trusted, outraged Colrain residents vowed to hang McClellan, along with another Colrain resident Major William Stevens, who had commanded the artillerymen at the Arsenal. The state had tried two Colrain men for treason and condemned them to death. McClellan's neighbors decided that if these two Regulators were to hang, then McClellan and Stevens would be hanged in retaliation. Thankfully, the two insurgents were pardoned, but widespread hostility made Colrain a difficult place to live for those who had fought with the government militia. Major Stevens ended up selling his property and moving to New York.(14)

Colonel McClellan was one of only a few in Colrain who opposed the Regulation.

More info

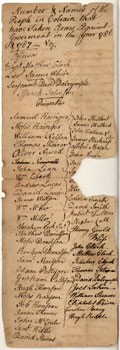

Ironically, some of the very men who vowed to hang Hugh McClellan later found themselves, in March of 1787, taking the Oath of Allegiance before him. As a Justice of the Peace, McClellan was authorized to receive their oaths. Worse, they were required to surrender their weapons to him. So many did so that McClellan's bedroom resembled an arsenal, with over 61 weapons stored there.(15)

Hugh McClellan and other Justices of the Peace administered oaths of allegiance to

former Regulators under the terms of the Massachusetts Disqualification Act.

Unlike Major Stevens, Colonel McClellan redeemed himself in his neighbors' eyes by working hard to obtain pardons for former Regulators as Shays' Rebellion wound down. Among them was Samuel Boyd. Like most Colrain men, Sergeant Boyd had fought with the Regulators; he was arrested and ended up in jail in Boston. Boyd was not only a neighbor of Hugh McClellan but also had served under him as a sergeant during the Revolution. Overcome with worry and in fear for her husband's life, Susanna Boyd approached McClellan to ask if he would intercede on her husband's behalf. Despite the bitter winter cold and ice, McClellan made the arduous trip to Boston on horseback to petition the General Court for Boyd's release. The newly-elected Governor, John Hancock later remarked, "Colonel McClellan, I believe if the devil himself should get into trouble, you would intercede, to have him set at liberty." The kindhearted McClellan replied, "Certainly sir,- I should, if he repented."(16)

Epilogue

Hugh McClellan never waivered in his support of the Massachusetts government, or of the new federal government created under the United States Constitution in 1789. He continued to disagree with his neighbors on political matters. McClellan was a strong Federalist, while many in Colrain favored Jefferson's Democratic Republicans. He ran unsuccessfully for Congress, but served several terms in the Massachusetts Legislature from 1801-1810.

In 1815 Hugh McClellan again lost his home to fire, along with all of his personal papers. He died in his sleep the following year, at the age of 73. His son Michael immediately rebuilt the house; it still stands in Colrain today.(17)

About This Narrative

Note: All narratives about people are, to the extent possible, based on primary and secondary historical sources.

See Further Reading for a list of sources used in creating this narrative. For a discussion of issues related to telling people's stories on the site, see: Bringing History to Life: The People of Shays' Rebellion

| Print | Top of Page