People

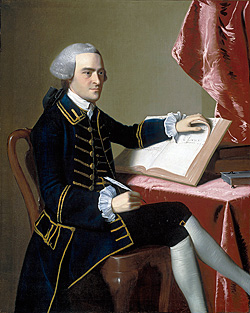

John Hancock

1737-1793

John Hancock

By John Singleton Copley, 1765. Photograph copyright September, 2008. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts Boston, MA

Prologue

John Hancock came from a family of ministers. His grandfather, John, served the Lexington, Massachusetts, parish for 54 years. His father, also named John, was a pastor in nearby Braintree. It soon became clear, however, that John, junior, was not bound for the ministry. Upon his father's death in 1744, eight-year-old John was sent to Boston to live with his uncle, Thomas Hancock. Thomas was an extremely successful merchant who had made a fortune in military contracts. With no children of his own, he was more than happy to put his wealth and influence to work for his late brother's eldest son. John Hancock received every possible advantage. He attended Boston Latin School and his admittance to Harvard was virtually assured. He also attended a writing school, where he developed the beautiful signature that would become part of one of the most famous documents in history.(1)

As expected, John attended Harvard, graduating in 1754. He spent the next several years watching and learning from his uncle. In 1760, Thomas sent John to London, where he met face to face the merchants with whom the House of Hancock did business. Living abroad also informed the handsome youth's sense of fashion; John indulged in the purchases and assumed the habits associated with men of wealth. When Thomas Hancock died in 1764, he left his entire business to John, making his 27-year-old nephew one of the wealthiest men in the North American colonies.(2)

A Famous Signature

Colonial politics, like trade, were often turbulent. They became more so when Britain tried to re-assert control over the colonies following the end of the French and Indian War in 1763. At first, John Hancock tried to remain aloof from the political aspects of British policy, although he criticized Parliament's early attempts to raise tax revenues from the colonies as bad for business. Hancock was soon convinced, however, that legislation like the Stamp Act attacked the essential liberties of the colonists. John's personal relationships likely encouraged his growing radicalism and frustration. A Freemason, Hancock attended the same Lodge as Samuel Adams, James Otis and Joseph Warren. All three men were strong Whigs, or liberty men, who denied Britain's right to tax the colonies without their consent.(3)

By 1775, British authorities considered John Hancock one of the principal leaders of what was looking increasingly like a colonial rebellion. In addition to actively drilling militia in Boston, "Colonel Hancock" served on the Boston Committee of Safety and was elected president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. By now, Hancock had realized that Boston was no longer safe for him and was staying in Lexington at the parsonage where his grandfather had lived many years earlier. In April, 1775, British soldiers marched into the countryside to seize gunpowder and other military supplies at Concord. They were also ordered to arrest Samuel Adams and John Hancock. Warned in the course of Paul Revere's famous ride that British troops were on their way, Hancock decided to stand with the small group of Lexington militia on the town green. Samuel Adams, however, convinced Hancock that it was his duty to leave since he would otherwise almost certainly be captured.(4)

War and the interruption of trade inevitably affected Hancock's business. The British army occupied Boston; his aunt and his fiancé(5) had been forced to flee the city with him. Hancock's demonstrated devotion to the cause of liberty combined with his wealth and status made him an obvious choice to serve as president of the Second Continental Congress in 1775. A Virginia delegate later praised his leadership as "Noble, Disinterested and Generous."(6) One of the first items of business was to choose a commander in chief for the American army encamped around Boston. Rich, well-connected and popular, Hancock seems to have thought the appointment might go to him, despite his lack of wartime experience. John Adams certainly believed Hancock expected to be nominated, recalling that

when I came to describe Washington for the new commander [instead of Hancock], I never remarked a more sudden and striking change of countenance. Mortification and resentment were expressed as forcibly as his face could exhibit them.(7)

Although relatively limited in his military knowledge and experience, George Washington was far more qualified than almost any other potential candidate, including Hancock. Time proved that the Congress had made the best possible choice, and Hancock fully supported Washington's appointment.

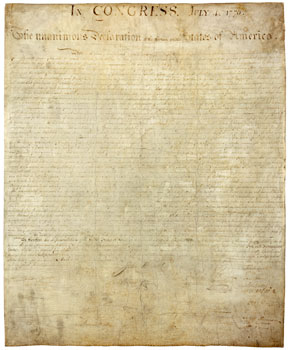

Through the spring of 1776, momentum for independence grew, culminating in the approval by Congress of "The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America."(8) As president of the Congress, John Hancock signed the Declaration on July 4. One of the most popular stories about Hancock is a remark he supposedly made as he signed:

There! John Bull can read my name without spectacles and may now double his reward £500 on my head. That is my defiance.(9)

On July 4, 1774, John Hancock appended his famous signature to the Declaration of

Independence.

More info

Hancock's place in American history was assured with the signing of the Declaration. He remained enormously popular at home in Massachusetts, where he continued to be elected to town and state offices. It did not hurt that he had a reputation for being a generous benefactor as well as a kind creditor who did not cruelly pursue distressed debtors who owed him money.

Popularity and Pardons

John Hancock was elected governor of Massachusetts in every election following the ratification of the new state constitution in 1780. Pleading ill health, Hancock resigned the governorship in January, 1785. In retrospect, growing popular unrest may have awakened Hancock's instinct for political self-preservation. Retaining the widespread admiration and popularity he craved would have been extremely difficult as resentment toward the General Court's heavy taxes festered in towns across the Commonwealth. Whatever the reason, Hancock was safely out of office when the storm that had been brewing over the previous year broke over the head of James Bowdoin, the newly-elected governor. Angry and alarmed, Bowdoin responded vigorously to what he insisted was a full-blown insurrection against the republic of Massachusetts. Bowdoin's name headed the list of well-to-do private citizens who pledged funds to pay the emergency militia called up to defend the state. Hancock's name was conspicuously absent from the list. As the state teetered on the brink of what many feared was becoming a civil war, he stayed above the fray and retained his popularity. Personal tragedy afflicted John and his wife Dolly, however, when their nine-year-old son, Johnny, fell while ice skating and suffered a fatal head injury.(10)

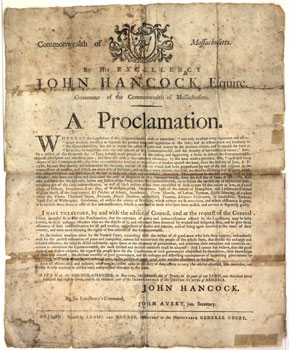

In the wake of the rebellion, John Hancock swept back into office, trouncing James Bowdoin at the polls by an enormous margin. As those favoring harsh measures against the insurgents dolefully predicted, the effects were immediate. Condemned insurgents were pardoned; in the end, only two men were hanged for looting. In June 1787, Governor Hancock issued a general pardon that negated the harsh terms of the Disqualification Act issued by the Bowdoin administration.

In his Proclamation, Governor Hancock offered all former insurgents "assurances of their indemnification for all past treasons, misprisions of treason and felonies, and of being again renewed to the arms of their country, and once more enjoying the rights of free citizens of the Commonwealth." The governor did specifically bar a handful of leaders, including Daniel Shays and Luke Day from the general pardon, as their "crimes are so attrocious, and whose obstinancy so great, as to exclude them from an offer of that indemnification, which is extended to those who have been misled, and are not so flagrantly guilty." By June, 1788, however, even Daniel Shays had received a pardon for his role in what would be remembered as "Shays' Rebellion."(11)

Governor Hancock cemented his popularity while annoying hard-liners like Samuel Adams

with a sweeping clemency policy.

More info

Governor Hancock had yet another moment in the spotlight during the Massachusetts ratifying convention in the winter of 1788. The convention was divided. It was by no means certain that the new constitution created at Philadelphia the previous summer would pass muster. Many delegates came from towns that had supported the rebellion; some, like Agrippa Wells of Bernardston, had personally taken up arms against the government. Rufus King was one of the delegates. King had attended the Philadelphia Convention and strongly supported the proposed Constitution. He admitted to James Madison that ratification was by no means a sure thing. A great deal depended, King wrote, on John Hancock. Hancock, however, had rarely attended the ratification debates, despite being elected president of the proceedings. Many believed that, like Elbridge Gerry and Samuel Adams , Governor Hancock disapproved of the proposed new federal plan. On January 30, Rufus King wrote excitedly to James Madison that it looked as though Hancock would come out in favor of the constitution. "[O]ur Hopes are increasing—if Mr. Hancock does not disappoint our present Expectations our wished will be gratified." King privately warned Madison that "his [Hancock's] character is not entirely free from a portion of caprice—this however is confidential…" On January 31, John Hancock fulfilled the hopes of King and other Federalists by attending and making a rare address to its members, calling on them to ratify the Constitution with recommendations for amendments. Samuel Adams followed Hancock's speech with a supporting speech of his own. King jubilantly reported to Madison, "We flatter ourselves that the weight of these two characters will insure our success."(12)

Epilogue

Massachusetts voters continued to elect John Hancock as their governor by overwhelming majorities. His health, however, continued to decline. When President George Washington came to Boston as part of a grand tour of the states in 1789, Hancock was too ill to attend the huge public celebration he had helped to plan. Some whispered that Hancock's vanity would not allow him to be upstaged in his own once-sovereign state by a President of the United States. The rumors were dispelled when Hancock personally called on President Washington, carried in by two servants. John Hancock was only 53 years old, but gout and other complications had turned him into a near-invalid. The owner of the most famous signature in American history died four years later, in 1793.(13)

About This Narrative

Note: All narratives about people are, to the extent possible, based on primary and secondary historical sources.

See Further Reading for a list of sources used in creating this narrative. For a discussion of issues related to telling people's stories on the site, see: Bringing History to Life: The People of Shays' Rebellion

| Print | Top of Page