People

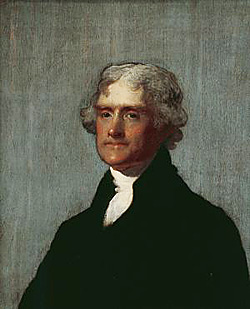

Thomas Jefferson

1743-1826

Thomas Jefferson

The Edgehill portrait by Gilbert Stuart, 1805/21. Jointly owned by, and courtesy of, Monticello, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, and the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institute, Washington, DC

Few people are linked as closely to the American Revolution and independence as Thomas Jefferson of Virginia. He formed his political opinions and philosophies in the crucible of the Imperial Crisis, and contemporaries quickly recognized Jefferson's flair for expressing in writing the beliefs and aims of the revolutionaries. In 1775, he became the youngest member of the Second Continental Congress. After drafting the Declaration of Independence in 1776, he served as the Governor of Virginia from 1779-1781. In 1784, Thomas Jefferson replaced Benjamin Franklin as the United States minister to France. When news of the turmoil in Massachusetts reached him in Paris, he wrote to his friend James Madison on January 30, 1787, "I hold it that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing." He went on to add that in his opinion, such rebellions were

as necessary in the political world as storms in the physical. Unsuccessful rebellions, indeed, generally establish the encroachments on the rights of the people which have produced them. An observation of this truth should render honest republican governors so mild in their punishment of rebellions as not to discourage them too much. It is medicine necessary for the sound health of government.”i(1)

Jefferson's optimistic reaction to the news of unrest in Massachusetts was characteristic. It also distinguished him from most other observers, including Madison, Abigail Adams and George Washington. It certainly set him apart from Massachusetts leaders like Samuel Adams, who declared that "the man who dares rebel against the laws of a republic ought to suffer death”(2), and General Henry Knox who feared that the Regulation was "a formidable rebellion against reason, the principle of all government, and against the very name of liberty"(3). Massachusetts governor James Bowdoin used still more alarming language to describe in a proclamation the armed confrontations in his state: "this high-handed offence is fraught with the most fatal and pernicious consequences, must tend to subvert all law and government; to dissolve our excellent Constitution, and introduce universal riots, anarchy and confusion, which would probably terminate in absolute despotism."(4)

In contrast to these alarming descriptions and predictions, Jefferson calmly reasoned that

The late rebellion in Massachusetts has given more alarm than I think it should have done. Calculate that one rebellion in 13 states in the course of 11 years, is but one for each state in a century & a half. No country should be so long without one. Nor will any degree of power in the hands of government prevent insurrections. France, with all it's despotism, and two or three hundred thousand men always in arms has had three insurrections in the three years I have been here in every one of which greater numbers were engaged than in Massachusetts & a great deal more blood was spilt.(5)

Nine days before the Regulators marched on the Springfield Arsenal, Jefferson wrote in their defense that

The people are the only censors of their governors: and even their errors will tend to keep these to the true principles of their institution…The basis of our government being the opinions of the people, the very first object should be to keep that right…Cherish therefore the spirit of our people, and keep alive their attention.(6)

The United States Constitution.

More info

Like John Adams, Thomas Jefferson was abroad in 1787 and thus was not present when the new federal Constitution was created in Philadelphia. Jefferson understood but did not wholly approve of the decision by the delegates to keep their deliberations secret, writing to John Adams in August 1787 that he was "sorry they [the delegates] began their deliberations by so abominable a precedent, as that of tying up the tongues of their members. Nothing can justify this example, but the innocence of their intentions, and ignorance of the value of public discussions." He endorsed their efforts, however, by adding that "I have no doubt that all their other measures will be good and wise. It is really an assembly of demi-gods." James Madison kept his friend well informed once the Convention adjourned and delegates were freed from their self-imposed silence.(7) Ultimately, Jefferson supported the Constitution but with reservations; he criticized the omission of a bill of rights, writing to Madison that this was a protection which "the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular, and what no just government should refuse, or rest on inference." Jefferson was less restrained in his comments on the Constitution to John Adams:

I confess there are things in it which stagger all my dispositions to subscribe to what such an assembly has proposed. The house of federal representatives will not be adequate to the management of affairs either foreign or federal. Their President seems a bad edition of a Polish king. He may be reelected from 4. years to 4. years for life. Reason and experience prove to us that a chief magistrate, so continuable, is an officer for life.(8)

Despite these reservations, Jefferson accepted an appointment from the first President George Washington to be the new government's first Secretary of State from 1789-1793. He then served as Vice President under President John Adams from 1797-1801. Jefferson was elected as the 3rd president of the United States in 1800, in an election so bitter and divisive that it went to the 36th ballot in the House of Representatives. Jefferson retired from public life when his second term ended in 1809. He died on July 4, 1826, fifty years to the day from the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, and on the same day as his old colleague and rival, John Adams.

About This Narrative

Note: All narratives about people are, to the extent possible, based on primary and secondary historical sources.

See Further Reading for a list of sources used in creating this narrative. For a discussion of issues related to telling people's stories on the site, see: Bringing History to Life: The People of Shays' Rebellion

| Print | Top of Page