People

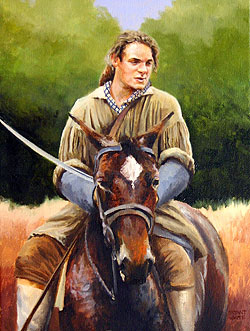

Henry McCulloch

1751-1819

Henry McCulloch

© 2008 Bryant White

Prologue

Henry McCulloch was born on March 3, 1751, in Pelham, Massachusetts. He was the last of six children born to Ann and Alexander McCulloch, a wheelwright and town treasurer. Ann died sometime before 1755, and in that same year, when Henry was four, Alexander married Sarah Peebles, the daughter of Robert Peebles, one of the two founders of Pelham. Alexander and Sarah added another two children to the family.

Henry was almost 30 years old and still unmarried when his father died in February of 1781. The distribution of his father's estate did not indicate any bequests of land to his sons; the house and land likely remained in Sarah's possession. As the youngest unmarried son, and apparently the only one still living in the area, Henry likely assumed the responsibility of caring for his step-mother and running the family farm. Three months after his father's death, Henry purchased 40 acres from Robert McCulloch, probably his uncle. (1) This is the land where Henry would eventually live with his wife and six children.

Taking Direct Action

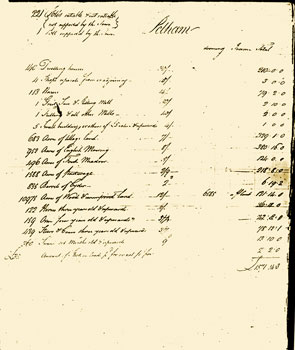

In the 1780s, Pelham was a small hill town community of farmers, numbering less than 1,000 people. Most farms consisted of a simple house, a few acres under cultivation, some hayfields and pasture, apple trees for the yearly pressing of cider, a woodlot, and considerable acreage of undeveloped land. Tax valuation records for 1784 list 221 polls and a variety of other buildings and land.

The 1784 tax list for the town of Pelham, indicates 221 polls, 140 dwelling houses, and 113 barns.

More info

Courtesy Historic Deerfield Library, Deerfield, MA

Like Henry's forebears, many residents had been poor tenant farmers in Scotland and Ireland. In Pelham, they led a meager existence, struggling to produce enough for their families despite poor soil conditions and harsh winters. Many had been fierce patriots during the just-ended American Revolution; their hatred of the British ran deep and support for the Crown was almost non-existent. (2)

In common with other western Massachusetts towns, Pelham experienced high taxes, surging inflation, and heavy financial burdens as the Revolutionary war wound down. The state legislature's new system of direct taxation, based on polls and real estate to pay the war debt, only added to farmers' already heavy financial burdens. Worse, the new taxes had to be paid in hard money, or specie, which was in short supply throughout the state, especially among farmers whose assets were tied up in land and livestock. A scarcity of good, arable land contributed to rising numbers of transients in area towns. By 1784, one third of voting males in Pelham in 1784 owned no real estate. There was a growing sense that the American Revolution had accomplished little. Now, instead of the Crown, an unresponsive state government located far away in Boston threatened their way of life and the freedom for which so many had fought and suffered. (3)

Henry McCulloch emerged at the center of growing unrest and protest in Pelham. In May of 1782, he was chosen at a town meeting to represent his community at a convention of area towns in Hatfield. Delegates at Hatfield and other conventions in Hampshire and Worcester County suggested a number of reforms to the new state constitution, but none were passed by the General Court. Similarly, between 1784 and 1786, dozens of Massachusetts towns, including Pelham, petitioned the General Court to reform the new state constitution.

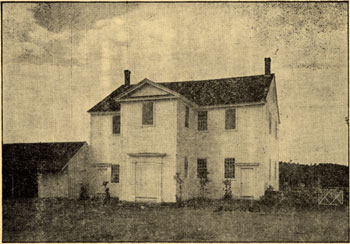

Pelham's meetinghouse, where Henry McCulloch and other Pelham residents attended worship and town meetings, is the oldest town hall in continuous use in New England.

More info

Courtesy Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, MA

Throughout the fall of 1786, a dangerous dance was taking place between the state government and western farmers. As times grew worse and the tax burden more and more insupportable, Pelham voters decided at a town meeting in January of 1786 to petition the state legislature for redress of their grievances. Despite the pleas for relief from Pelham and other towns, the legislature that met over 60 miles away in Boston adjourned without addressing their concerns or providing any relief. Frustration turned to anger. How would they pay debts and taxes without hard money? Why was the seat of government in Boston, and not more centrally located, sparing them the high cost of travel? Why were there so many layers to the court system, and why were court fees so high? In fact, what good was the 1780 state constitution? Was this what they had fought for in the American Revolution?

By the summer of 1786, the farmers of Pelham were losing patience. Henry may have been one of the representatives from 50 Hampshire County towns who met again at a convention held in Hatfield, Massachusetts, in August. The Hatfield Convention adopted 21 articles, 17 of which necessitated radical change in the state government and, most likely, a new state constitution. The Convention urged peaceful means of gaining the reforms its delegates sought. Only a week later, however, a group of Pelham men disregarded the Convention's recommendations to stick to peaceful means. Like hundreds of others, they threw caution to the wind, and converged upon the Northampton, Massachusetts, courthouse. Those who had them came armed with muskets, swords, or bludgeons; others arrived without weapons. (4) The crowd, led by Captain Luke Day of West Springfield, succeeded in getting the Court of Common Pleas to adjourn without transacting business, and to "continue all matters pending" in November.

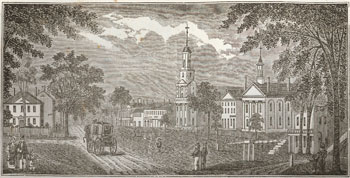

In September, 1786, a group of men from Pelham, Amherst and surrounding towns succeeded in closing the Court of Common Pleas. This depiction of the Northampton courthouse was created by John Warner Barber in the 1830s.

More info

Courtesy Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, MA

Court disruptions and harassment of judges by thousands of men calling themselves "Regulators" spread across the state, especially in central and western Massachusetts. Regulators led by Daniel Shays and Luke Day closed the Springfield Supreme Judicial Court in September and the Court of Common Pleas that December.

The state responded by cracking down with the Militia Act and the Riot Act. Suspension of the Writ of Habeas Corpus swiftly followed. This last action enabled the legislature to order suspects to be imprisoned anywhere in the Commonwealth and to jail them indefinitely without charging them. These actions enraged the Regulators, who began organizing and drilling in organized companies. The government responded by calling out the militia, labeling Regulators "insurgents" and considering their actions a rebellion. In early January of 1787, Governor Bowdoin called up a force of 4,400 men, under the command of General Benjamin Lincoln, to put down the rebellion, and issued arrest warrants for 16 rebel leaders. Armed conflict seemed imminent.

Disaster at the Arsenal

On January 24, 1787, Henry McCulloch was among about 1,400 Regulators who marched with Daniel Shays to the Springfield Arsenal. Like most of his fellow townsmen who took up arms for the Regulator cause, he was young and unmarried. Unlike many of them, Henry had not fought in the American Revolution. Nor did he share ties of blood and marriage with other Regulators. In this Henry was the exception rather than the rule; 40% of Pelham Regulators had a brother or half-brother who was also an insurgent, and there were numerous other kin-based relationships among the group as well. (5)

Henry was known to be a wild, colorful young man, with a flair for the dramatic. Letters and petitions supporting him after the government put down the Regulation, made mention of his "rashness," youth, vulnerability to alcohol, gullibility, foolishness, irresponsibility, and his propensity to "show off" on his horse while wielding a sword. Perhaps it was with such bravado that Henry joined the march to the Arsenal. And perhaps when the Arsenal canons were fired and blood was drawn, he,+ like others, retreated in shock that the march had come to bloodshed.

When the Arsenal canons fired, cannonballs and grapeshot tore into the first men in the advance. Detail from Bloody Encounter - Regulators

© 2008 Bryant White

Like his comrades, Henry was shocked at the ferocity with which the government militia holding the United States Arsenal fired upon the advancing Regulators. Dozens of rounds of grapeshot and cannon balls ripped through the middle of the advancing column, killing three men outright in the most gruesome manner and wounding 20 more. McCulloch joined the disorganized flight from the militia they regarded as no better than murderers. Daniel Shays led what remained of the Regulator force first to the Pelham hills, and then to Petersham, Massachusetts. Meanwhile, General Benjamin Lincoln arrived from Boston with additional government militia. Lincoln relentlessly pursued the remaining Regulators, routing them at Petersham on February 3, 1787. From there it was every man for himself. Like Shays, Henry slipped across the border into Vermont in the aftermath of the Petersham attack.

Sentenced to Death

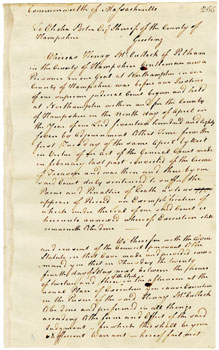

Henry McCulloch returned to Massachusetts a month later to surrender himself. He was immediately arrested. In April, Henry and five other men were tried for treason. All were found guilty and sentenced to death. Three of the men were soon pardoned and released from prison. However, Henry and Jason Parmenter of Bernardston, Massachusetts, were condemned to hang for "most wickedly and traitorously devising and conspiring to levy war against this Commonwealth." (6) They were confined to the jail in Northampton to await their fatal day.

Henry McCulloch was found guilty of treason and sentenced to death for his part in the insurrection.

More info

Courtesy Massachusetts Archives, Boston, MA

While in prison, Henry wrote to Governor Bowdoin to plead for his life. In his letter, he expressed sorrow and remorse for his actions, and asked for mercy:

"Your petitioner went from Home unarmed and was persuaded, merely for Show, to take an Old Cutlass just before the Attack at the Arsenal, and…was guilty of uttering divers foolish and wicked expressions for which he is heartily grieved and ashamed…."

Henry's widowed step-mother petitioned the Governor to spare her son's life, blaming Henry's troubles on strong drink and questionable company; she begged for mercy for herself, as well as her son: "…may the Tears and prayers of a poor widow whose only support he is, be heard … I am an old woman…what shall I do, when my Son is no more? where shall I go for support?"

Many people in Pelham and surrounding towns petitioned Governor Bowdoin to show compassion and spare Henry. Letters written on his behalf emphasized his youthful inexperience, community pressure to participate, and the influence of others who took up arms. Major Ebenezer Mattoon, justice of the peace in Amherst, was typical in his opinion that Henry was just a "tool of the rebel leaders…" In exchange for a pardon for Henry, petitioners from Pelham assured the Governor that they "would use their utmost Influence in future, in order to promote and Secure a due Submission to Government, and Obedience to the Laws."

On June 21, 1787, despite the many moving appeals on their behalf, Henry McCulloch and Jason Parmenter were led from the Northampton jail to be hanged on the gallows. Since long before dawn, crowds of people had been converging on Northampton on horseback and in oxcarts. Armed men carrying rifles and ample ammunition, led by General Shepard, lined the streets. McCulloch and Parmenter listened to the Reverend Moses Baldwin of Palmer deliver their final sermon and then marched to the gallows. Men, women and children looked on as the sheriff stood ready to do his duty. Surely some hearts sank. Would this governor and this legislature really allow the hanging of men whose only real crime had been protest against what many of them had found unendurable? (7)

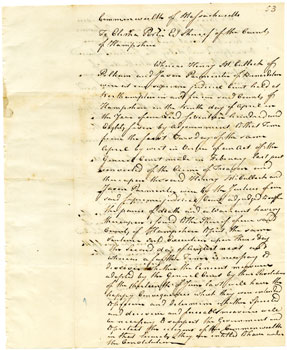

The two men stood with ropes around their necks; the fateful moment approached. Then, at almost the last possible moment, Sheriff Elisha Porter of Hadley produced a document announcing a stay of execution to August 2. The two shaken prisoners returned to jail. This drama illustrated the government's determination to "have its cake and eat it too." When newly elected governor John Hancock had raised the possibility of a pardon, the Council agreed to a compromise. The guilty parties would be marched to the gallows and all would proceed as if they were going to be hanged. The Council stipulated that only at the last minute would they be granted a reprieve. Thus, "On Thursday last," reported the Independent Chronicle, "Jason Parmenter and Henry McCulloch had LIKE to have been hanged." (8)

Henry McCulloch and Jason Parmenter were reprieved at the last minute.

More info

Courtesy Massachusetts Archives, Boston, MA

Epilogue

On September 12, Governor Hancock pardoned Henry and ordered his release. When he returned to his farm and the support of his family, the town voted to help him get off to a good start by "remitting" the back state and town taxes he owed. (9) That December, Henry married Martha Hamilton and settled down to the life of a husband, father, and farmer. Between 1788 and 1802, he and his wife had six children. During these early years of his marriage, Henry remained a modest farmer, ranking near the middle of the town's tax list in 1795. (10)

In later years however, the economic downturns that plagued Pelham in the years following Shays' Rebellion hurt Henry as well. By the end of the first decade of the new century, his name appeared among the bottom fifth of the town's taxpayers. In 1800, he sold off 40 acres. By 1807, the town tax list assigned no value to Henry's real and personal property. (11) Perhaps at this time, Henry moved his family in with his step-mother or rented from his uncle or cousin.

By 1810, the McCullochs were among the poorest residents in town. In 1812, at the age of 61, Henry was imprisoned for debt in the same Northampton jail where he had awaited execution nearly a quarter century earlier. This time he was no longer a rash and impetuous 30-year old marching to attend conventions and close courts, but a 61-year-old father sent to jail for failing to pay his debts. Although town records do not record his death or burial, an 1894 genealogical record indicates that Henry "died in 1819 in Pelham." (12)

About This Narrative

Note: All narratives about people are, to the extent possible, based on primary and secondary historical sources.

See Further Reading for a list of sources used in creating this narrative. For a discussion of issues related to telling people's stories on the site, see: Bringing History to Life: The People of Shays' Rebellion

| Print | Top of Page