People

Jonathan Judd

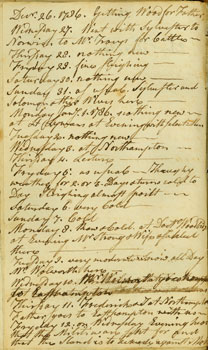

We are unaware of any surviving portrait of Johnathan Judd

Prologue

Jonathan Judd was a merchant and well-respected resident of Southampton, Massachusetts. The son of Southampton's first minister, Jonathan attended Yale and graduated in 1765, but was not interested in following in his father's footsteps. After teaching school in nearby Hatfield for a few years, Jonathan decided to try his hand at business. He opened a store in his father's home in Southampton in 1769. Perhaps it was this change in his circumstances that led Jonathan to begin keeping a journal in February 1768, in which he carefully recorded the events occurring in his world, from the mundane to the remarkable. He reported on the political and social upheavals of the American Revolution as he perceived and experienced them, as well as the turmoil of 1786-87 known as Shays' Rebellion.(1)

For over thirty years, Jonathan Judd recorded his impressions of the events of the day,

including Shays' Rebellion, in his private journal.

More info

A Cautious Revolutionary

Jonathan's situation as a young man just starting a business may have contributed to his reluctance to engage in political controversy. His journal, however, reveals his essential and genuine conservatism in the years leading up to the outbreak of war in 1775. He recoiled from the mob violence that all too frequently attended pre-revolutionary protests. After a trip to Boston to purchase inventory for his store in the fall of 1769, Jonathan wrote angrily that

No Man may speak his Mind unless he thinks as the populace Say…Last Saturday Night an Informer was tard [sic] and featherd and carried through the streets for three hours(2)

Jonathan also disapproved of those closer to home who flaunted extreme Whig views such as Timothy Clark, a Southampton tavern keeper. Jonathan saw no reason to assist Clark in erecting a liberty pole, noting acerbically "had it been a more general thing I should have helped but not to raise a tavern sign for Timothy Clark."(3)

Despite his clear distaste for unruly popular politics, Jonathan found himself drawn into the revolutionary movement. In 1774, he was appointed to Southampton's Committee of Correspondence, which produced recommendations for supporting Boston as the city suffered under the punishments applied by Parliament in the wake of the Boston Tea Party. As part of its so-called Intolerable Acts, the British government also clamped down on the colony through the Massachusetts Government Act. The act alienated even conservatives like Judd and inflamed more radical Whigs. A mob of 3,000 men brandishing staves surrounded the Springfield Courthouse on August 31, 1774 to protest the royal governor's take-over of the colony's judiciary. In his journal, Jonathan contemplated with mingled fear and chagrin a world in which law and order seemed in short supply:

All opposition was in vain every Body submitted to our Sovereign Lord the Mob Now we are reduced to a State of Anarchy have neither Law nor any other rule except the Law of Nature.(4)

Against his better judgment, Jonathan accepted an unsought appointment as a Captain of the provincial militia in 1772. He resigned his commission as soon as possible and resolutely refused to serve in either the government militia or the minuteman companies springing up alongside. Judd did, however, assist in recruiting soldiers from Southampton and in disciplining deserters when the war began.(5)

By 1782, the Revolution had dragged on for seven years. Fiscal problems and hostility to the new Massachusetts constitution brought hundreds of men out once again to close Hampshire County courts. Jonathan worriedly noted the gathering of mobs. The state called upon the militia to defend the courthouses, and arrested the leader of the protests, Samuel Ely.

"The Tyranny of this Mob"

In late August 1786, mobs were again marching on courthouses. On August 28, Jonathan wrote, "Noise of the Mob they will come but how many no body can tell." He witnessed the court closing at Northampton led by Captain Luke Day of West Springfield. Judd wrote with renewed frustration and outrage that "all is again aflout No Law nor Order prison full of Criminals but none can be punished." He confided in the privacy of his journal that "Monarchy is better than the Tyranny of this Mob." (6)

Jonathan Judd had had enough. Very early on September 26, 1786, he accompanied a group of about seventy militiamen to Springfield "to support the government." An agreement allowing "the Mob" to "march and countermarch through the town" and the adjourning of the court helped prevent violence. The peaceful outcome did not improve Judd's mood, for the situation remained hostile and tense. He somberly wrote, "A very sorrowful day Brother against Brother Father against Son The Mob threten Lives of all that oppose them."(7)

At Springfield, Jonathan Judd witnessed the standoff between the government militia and

the men he persistently called "the mob."

That winter, Jonathan worriedly recorded the movements of militia and insurgents. Sleigh loads of men and supplies traveled to Springfield, where the militia under General William Shepard of Westfield guarded the United States Arsenal at Springfield. Like his neighbors, Jonathan was aware that the insurgents under Captain Daniel Shays were on the move, but he did not know where or when: "Hear Shays is collecting a party at Pelham and that they are marched or marching forwards here. perhaps to Palmer."(8) Two days later, Judd was able to report that Shays' men had been dispersed at the Arsenal, and that four of the insurgents had been killed. The situation seemed to be changing hourly; on January 29, Jonathan simply wrote, "Confusion" before reporting that General Benjamin Lincoln's militia was planning to pursue Shays to Pelham. (9)

General Lincoln's rout of Shays' men at Petersham on February 4 signaled the end of the rebellion. Jonathan wrote with relief that the "Insurgents are broken and disheartened if not suffisiently Conquered…Many People take Oath this Week." Shays and "a few others" had fled to Vermont, while thousands of former insurgents came forward to receive pardons under the terms of the Massachusetts Disqualification Act issued on February 16. On March 2, 1787, Judd reported a final, bloody confrontation between government militia and insurgents that had taken place at Sheffield in Berkshire County the previous week.(10)

Epilogue

The creation of a new federal government and a more settled economy helped to establish the political stability Jonathan craved. In the years following Shays' Rebellion, he remained an active and respected member of Southampton. He served in several town offices, including selectman and town clerk. He never married. Friends and family mourned his death in 1818 at age 75. The monument they erected to his memory extolled Jonathan Judd as

an honest man, a good citizen, an upright merchant, a judicious Magistrate, and faithful and benevolent in the duties of life. His virtues are still fondly remembered by his friends, and his brothers and sisters have the melancholy pleasure of bestowing this last tribute of affection to his worth, out of a small part of the property left them by him(11)

About This Narrative

Note: All narratives about people are, to the extent possible, based on primary and secondary historical sources.

See Further Reading for a list of sources used in creating this narrative. For a discussion of issues related to telling people's stories on the site, see: Bringing History to Life: The People of Shays' Rebellion

| Print | Top of Page