People

Seth Catlin

1734-1798

Seth Catlin

© 2008 Bryant White

Prologue

On a warm July evening in 1774, Seth Catlin, accompanied by his friends Elihu Ashley and Phineas Munn, stealthily sawed off the 45-foot "Liberty Pole" that had recently been erected in front of David Field's Deerfield store. The "Sons of Liberty" erected liberty poles, sometimes topped by liberty caps or flags, as signs of solidarity against the British government.

Raising the L

iberty Pole

in New York City. Liberty poles like this one in New York City sprouted throughout the colonies in the years leading up to the American Revolution. Erecting a liberty pole in Deerfield was a politically charged act that pleased Whigs and dismayed Loyalists like Seth Catlin.

Pen and ink drawing by Pierre Eugene du Simitiere, New York, 1770. Courtesy Library Company of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA

Seth and his friends criticized such poles as misguided efforts by the Whigs to promote dangerous political beliefs. Liberty men foolishly "thought the Erection of a Liberty Pole would have ye most happy tendency of restoring and Establishing Peace and Harmony between ye Mother Country and ye Colonies." (1)

Cutting down a liberty pole was only one of several acts Seth Catlin carried out in support of the Crown. A month later, he faced an angry mob determined to close the Court of Common Pleas in Springfield. Moses Harvey of Montague "much abused" an angry and frightened Seth Catlin for daring to open the court in his official capacity as a Justice of the Peace and officer of the court. It was a humiliation that Seth Catlin would not forget. It reinforced a life-long commitment to strong government and a corresponding contempt for mobs led by lawless men like Harvey. (2)

Seth was born in 1734, the fourth of eight children born to John and Mary Munn Catlin. He was the second oldest son. While in his early twenties, he served as a drummer in his father's company in the French and Indian War in 1757-58. He was at the battle of Ticonderoga under General Abercrombie in 1758, and after his father's death that same year, he became a 2nd lieutenant under General Amherst in the campaign of 1759. (3)

In 1762, at age 28, Seth married Abigail Denio, also of Deerfield. They lived in the home where he had grown up, and which he co-owned with his mother and brother, Joseph, until 1764 when Seth became the sole owner. He kept a licensed tavern in the house from 1762 through 1773. Sometime after 1764, he built himself a new house. Seth and Abigail started their family in 1763. Seven daughters and one son lived to adulthood. A 1773 table listing lots and acreage by owner reveals that Seth and Joseph jointly owned approximately 1,535 acres. Of a total 41 Deerfield landowners, only one other man owned more Deerfield real estate than the Catlins. (4)

Life was difficult for anyone suspected of Loyalist leanings during the tumultuous years leading up to the Revolution. Even respected and well-regarded men like the Catlins were subjected to harassment and threats. Like Seth and his young friend Dr. Elihu Ashley, John Williams was a known Loyalist. In January 1775, a mob composed of Whigs, or Patriots, gathered outside of Williams' house next to his store on the main street in town. They were intent on breaking in, but Williams had already secured assistance from Loyalist friends. When the mob tried to break down the front door, Seth Catlin appeared in a window above the door, declaring his intention to shoot into the crowd if they did not cease their action. The mob quieted, knowing Catlin was a military man capable of making good on his threat. (5)

A military roster from 1777 lists Seth Catlin has having been "draughted" to serve in the Revolution; however, in 1778, he appeared on a list of men who refused to serve. A friend would later write about Catlin, "From sincere and honest motives he was opposed to the war of the Revolution, but he often refused important offices in that war from the British government, as also from his own country." (6)

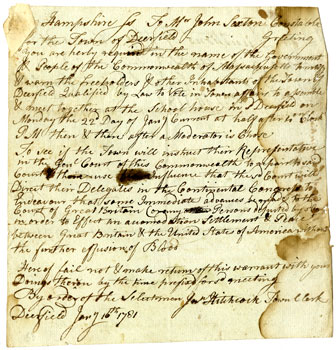

By February of 1781, the war had dragged on for six long years. Loyalists and Whigs struggled to control Deerfield's government. At a town meeting in 1781, the Loyalists gained the upper hand and issued a town warrant instructing the town's representative to urge the Massachusetts Legislature "to Effect an accomodation Settlement & Peace between Great Britain & the United States of America without the futher effusion of Blood."

In the midst of the American Revolution, Seth Catlin and other Deerfield Loyalists supported a town meeting warrant urging the Massachusetts Legislature to seek peace with Great Britain.

More info

Courtesy Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, MA

When the Whigs regained control, they undid all that the Loyalists had done. However, the Loyalists were so vocal in their opposition to the war that a hearing was held in Boston in front of both houses which included the following report on their activities:

Whereas it appears by Instructions given the Representative of the Town of Deerfield, and also by representations made to the Gen'l Court, that Divers persons, Subjects of the Commonwealth, are Disaffected to the Independence of the United States in General, & of this in particular, and are artfully propagating the most dangerous principles within the same, and are using their utmost efforts to prevent furnishing supplies of Men and provision for the army of the United States, and to withdraw the good people of this Commonwealth from their allegiance to the government thereof. (7)

The Massachusetts General Court recommended that the attorney general prosecute any offenders. Upon examination, the General Court determined

that there are just grounds of suspicion that the said John Williams, Seth Catlin and Jonathan Ashley are unfriendly to the Independence of the United States. Therefore, Resolved, That the Governor with the advice of the Council be, and he hereby is requested to lay these men under such restrictions, as that the Commonwealth receive no injury from them or either of them. (8)

The three men were jailed in Boston to be held until September, when they were to appear before the Superior Court in Springfield to answer to "their conduct in the war with Great Britain." By May, the prisoners had appealed for release. Seth Catlin claimed great hardship due to "having a wife and six daughters, and one son of 8 years, who almost Daily depend on his Daily Earnings for their Support who have no Rescoures to Obtain the Shortest Relief but by his Immediate presence." The three prisoners were not allowed their freedom and appealed again in April. They were released on 2,000 pounds bail each, provided they appear at the next Supreme Court sitting in Springfield and exhibit good behavior "towards all the good people of this Commonwealth & particularly that they will not do or say any thing to the Injury of this or the United States, against the Independence thereo." Elihu Ashley's older brother Jonathan was in especially poor health and died several months after his release. (9)

The animosities generated in the years leading up to and during the war persisted after the arrival of peace in 1783. A severe depression followed a brief post-war boom.

Sales at John Williams' store in Deerfield dropped dramatically as the post-war boom became a bust. Detail from Boom and Bust

© 2008 Bryant White

As times grew harder, dozens of towns petitioned the Massachusetts General Court for relief. County conventions criticized the heavy taxes and hard-line fiscal policies of the state government and called for an amended state constitution. As in the years before the Revolution, angry men formed militia companies, drilled on town commons and marched to close the judicial courts. Seth Catlin likely viewed the escalating tension with apprehension and contempt. Unlike the 1770s, however, most Deerfield residents did not join the Regulators who took up arms against the government. Instead, men like Joseph Stebbins who had led mobs in 1774, now joined forces with former Loyalists like Seth Catlin to oppose what they considered a full-blown insurrection against lawful government.

In September 1786, Seth Catlin joined a company of men who marched to protect the Supreme Court at Springfield. As he had 12 years earlier, Catlin faced Moses Harvey and a mob determined to close the court, and once again, the mob succeeded; the justices adjourned the court. (10)

In September 1786, Seth Catlin again confronted an angry mob when he marched with other Deerfield men to protect the Supreme Court at Springfield from "violent and riotous proceedings."

More info

Courtesy Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, MA

Punishment and Appeasement

During the winter of 1787, Deerfield hosted almost 1,000 government militia called up to put down the armed uprising government supporters were calling a rebellion. Catlin put up 52 of these men and provided three gallons of West Indies rum to the militia stationed at the United States Arsenal at Springfield. He likely rejoiced in the collapse of armed resistance following the bloody confrontation at the Arsenal between General William Shepard's government militia and the Regulators led by Daniel Shays and Eli Parsons.

In April, 1787, Seth Catlin joined town officers across the state in taking an oath that he would "bear true Faith and Allegiance, to the…Commonwealth, and that I will defend the same against traiterous Conspiracies and all hostile Attempts whatsoever." In the same oath, Catlin promised to "renounce and abjure all Allegiance, Subjection, and Obedience to the King of Great Britain—and every other foreign power whatsoever. As a Justice of the Peace, Seth was required to administer oaths of allegiance to former Regulators who swore their loyalty to Massachusetts in exchange for a conditional pardon. In February, Catlin wrote to a known Regulator, Lieutenant James Stewart of Colrain, Massachusetts, informing him that he would be at Reuben Wells' tavern in Greenfield at 10 am the following Thursday to administer the oath to any insurgents who had not yet come forward. Catlin sternly instructed Stewart to let his men know "that now is the Day of Grace — and it may be soon over." Catlin must have felt a grim satisfaction when Moses Harvey, the man at the head of the mob who had "much abused" Catlin at the Springfield Courthouse in 1774, was sentenced to sit on the gallows for an hour with a rope around his neck for the crime of leading a mob against the same courthouse in 1786. (11)

Seth Catlin, who had been imprisoned during the American Revolution for his suspected loyalty to England, administered Massachusetts oaths of allegiance to former Regulators who had taken up arms against the state government in 1786 and 1787. Detail from Taking the Oath

© 2008 Bryant White

It is not known what Seth Catlin thought about the proposed Federal Constitution, but he likely shared the framers' fervent hope that the new government would "ensure domestic tranquility." Catlin continued to serve as a Deerfield Selectman and Justice of the Peace periodically through 1798. He also served as a Deerfield representative to the Massachusetts legislature in 1790, and again in 1795-96. In March of 1798, Catlin was crushed against the side of a stall by one of his prized horses and died soon after. (12)

Epilogue- A Man Who "Could Never Pass a Scene of Distress on the Other Side"

Seth Catlin, a dedicated Loyalist, was known throughout his life to be a man of conviction, action, and morals. It was said that he was "too much of a gentleman to be a rich man." When confronted by Loyalist friends after naming them in a judicial investigation, his retort was, "You didn’t expect I was going to lie did you?" Yet, he steadfastly faced down a mob to protect a fellow Loyalist and neighbor. Perhaps the finest words of praise come from his contemporary, Reuben Bardwell, who wrote of Seth Catlin in 1837, "He was a man of urbanity, and strict integrity, but of very strong feelings; could never pass a scene of distress on the other side, or suffer guilt to pass with impunity." (13)

About This Narrative

Note: All narratives about people are, to the extent possible, based on primary and secondary historical sources.

See Further Reading for a list of sources used in creating this narrative. For a discussion of issues related to telling people's stories on the site, see: Bringing History to Life: The People of Shays' Rebellion

| Print | Top of Page